A Positive Trial Sets the Alzheimer’s World Abuzz. I'm Not Convinced.

Does lecanamab really merit all the excitement?

You may have heard: AN ALZHEIMER’S DRUG ACTUALLY HAD A POSITIVE TRIAL!!! The news on Biogen/Eisai’s lecanemab was “exciting,” “shocking,” or at least “promising,” depending on your media outlet of choice. However, just because we set the bar almost impossibly low after the train wreck of the FDA’s approval for Biogen’s similar Alzheimer’s med, Aduhelm, I don’t think we should be pumping up the hype machine for this modestly positive outcome with lecanemab. I very much doubt your grandma will ever end up benefiting from this medication.

I am not alone with my concerns; many have pointed out the questions swirling around this trial (note — I am neither confirming nor denying that this picture was taken of me this morning after my wife’s alarm went off at 5:15AM):

The biggest question involves whether the modest improvement seen in the 1,800-patient trial is clinically meaningful. Yes, it was statistically significant; the trial was large and adequately powered to find a small difference between the lecanemab group and placebo. However, I could probably dream up a modestly effective blood pressure medication that requires an IV infusion every two weeks, test it on 1,800 people with high blood pressure, and find that it reduces mean systolic blood pressure by 3 points, with a confidence interval from 2.5 to 3.5 — but that doesn’t mean the juice would be worth the squeeze.

All we have to go on at this point are Biogen’s “topline” results. A press release is not the best way to absorb medical trial data; think skimming the cream off the “top” of a trial’s data and not worrying about all that sour buttermilk left behind. It’s a means to pump up regulators, shareholders, and future partners (i.e., physicians and their patients) before we get to comb through the rest of the messy data later, and set positive expectations early. So, to remind everyone: the modest 27% improvement reported is Biogen’s best shot at promoting their product. What about linked secondary outcomes like cognitive scores and brain scans which were only disclosed to be statistically significant without further details? I am going out on a limb to guess that when the Big Reveal comes next month at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Congress, they are going to be even less exciting, shocking, and promising.

Given that perspective, just how “promising” were these results? The study employed the catchily-termed Clinical Dementia Rating - Sum of Boxes (“CDR-SB”) as their measurement tool for the primary study outcome. This is not a “hard” outcome like blood pressure or tumor size which can be objectively measured; it is a sum of subjective ratings based on a clinician interviewing a patient (and their family members). While not a tool I use in my clinical practice, there seems to be fairly broad agreement amongst neurologists that a drop of 1-2 points has practical significance, and a relative improvement of 0.5-1 points implies clinical utility. This score declined about 1.7 points for the placebo group over the 18 months of the study; in other words, their dementia worsened to a significant degree. Those receiving lecanemab? They dropped about 1.25 points, so their dementia also worsened significantly, just by 0.45 points less. Yes, two IV infusions at grandma’s friendly neighborhood infusion center every month — 36 trips over a year and a half — all for the questionable benefit of a not-quite-clinically-significant reduced loss of cognitive function.

Raise your hand if you’ve ever had to take a demented relative to the doctor or hospital. Fun stuff for everyone, right? Twice a month is rather a lot; twice as much as Aduhelm promised, in fact. And each visit has the added adventure of not just your average trip to the doctor, but includes an IV start, and keeping grandma still until the infusion is over — no picking at that catheter allowed!

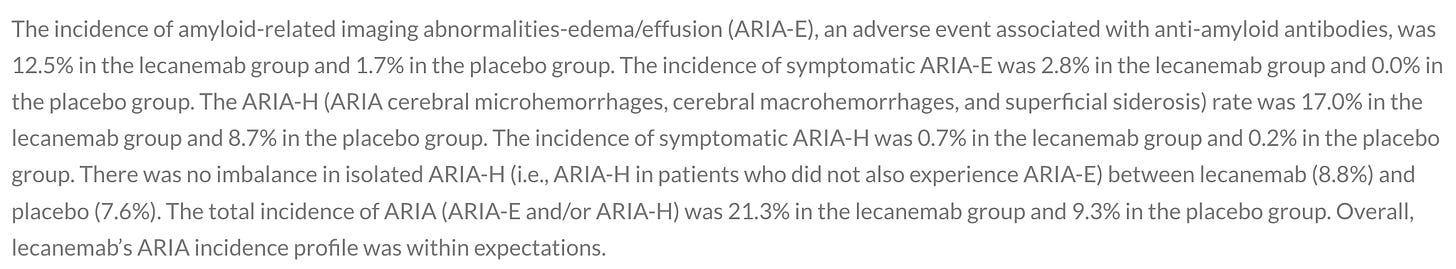

For this periodic unpleasantness, we also get some serious safety concerns. Aduhelm had a far worse safety profile, but lecanemab is not clear of worry. Data on tolerability was not released, but the known class effect of these anti-amyloid medicines is something called Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities, either involving brain edema (“ARIA-E”) or small hemorrhages (“ARIA-H”). ARIA-E and ARIA-H are thought to be related to breakdown of the blood-brain barrier from this class of medications. The press release told us this:

Uh, okay. Over 20% of participants receiving lecanemab had this adverse event detected — but no worries, since it “was within expectations!”

While the majority of those affected lacked symptoms like headache, dizziness, or confusion, left unanswered is what these radiologic findings would lead to over a prolonged course of time. Given that microhemorrhages from a disease like cerebral amyloid angiopathy are strongly associated with dementia, the long-term outcome for the asymptomatic majority might not be great, either.

We’re also left with the dilemma of what to do with this information for those affected. Here is the protocol described from the Aduhelm trials for managing these findings, which, again, affected over 20% of those receiving lecanemab:

Monthly brain MRIs until resolution? A brain MRI involves lying very still in an enclosed scanner for over half an hour. More relaxing down time for grandma. They also cost north of $1000 in my neck of the woods.

Which brings us to one last problem with all this professed enthusiasm for lecanemab. Cost. The numbers being bandied about are well lower than originally pronounced, likely due to Medicare’s unwillingness to shell out for Aduhelm after the FDA’s inexplicable approval of that anti-amyloid medication. However, $10,000-$35,000 per year is a massive potential expenditure when one considers that over 6 million Americans are thought to be living with dementia. Broad adaption of lecanemab could add a number with a lot of zeroes after it to our Medicare budget.

Of course, my skepticism could end up being misplaced. We don’t have the data, but it’s possible that humble divergence between placebo and lecanemab groups was growing at 18 months, and might continue to grow at 3 or 5 years and amount to a real difference. If people are treated early in their disease course, when CDR-SB scores are lower, and small changes are more meaningful, lecanamab’s impact would be greater. It’s also possible that targeting, or excluding, patients with the known Alzheimer’s genetic risk factor, APOE ε4, might improve results (although APOE ε4 carriers also are most prone to ARIA when treated, so that could get complicated). These things are possible, and lecanemab could end up being a moderately useful drug when the dust clears.

However, I don’t think that’s likely. It’s more likely these results will be the best we will ever see, much like Aduhelm had one positive study, with nearly identical results to lecanemab’s, before the next trial flopped. If patients were able to detect whether they got the active medication through side effects, or certainly if they were told they had imaging abnormalities, their perceptions and those of the clinicians interviewing them might have changed enough to skew their (subjective) CDR-SB scores that small amount.

It’s important to remember that the reason why everyone voiced terms like “shocking” and “unexpected” for these results was that this whole approach to Alzheimer’s has been in question given a decades-long track record of failure to record clinical wins. Some are describing this trial as “proof” of the “amyloid hypothesis” — that amyloid plaques are the primary pathology behind Alzheimer’s dementia. However, it remains quite possible that this trial was a one-off anomaly, and trying to reduce the burden of amyloid plaques will never lead us to the Promised Land of curing Alzheimer’s. I’ll add that my confidence in this field was certainly not enhanced by the recent allegations that a whole subset of research on the amyloid hypothesis had actually been faked.

The big picture is that Alzheimer’s dementia is most likely a highly complex and individually variable inter-related mix, including genetic influences, metabolic and cardiovascular disease, psychologic health, and neuroinflammation. Beta-amyloid proteins folding up into plaques probably fits in there somewhere. Harnessing antibodies to erase amyloid plaques long after their creation is probably not the Holy Grail medicine seeks.

Dr. Dale Bredesen, Director of the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at UCLA, rightfully has taken a lot of heat for his confident (and expensive) program for treating Alzheimer’s dementia naturally. Presenting small studies without control groups and asserting that nearly all participants actually improve their cognitive status by following his mostly common-sensical regimen of improving sleep and diet, exercising regularly, correcting thyroid and B-12 imbalances, etc. is a country mile from real science. That said, could changes of that nature be implemented with less effort than dragging a demented parent to an infusion center 36 times in 18 months, at a fraction of the $200,000+ price tag of lecanemab? Absolutely. Might those people have declined modestly less than the placebo group, too?

I’d bet on it. And, stock price be damned, I’d bet against lecanemab.

I’m definitely in agreement that this trial is barely better than a flop, but biogen will do everything they can to gain approval and sell billions of dollars worth to desperate families.

Consider that the 0.45 point higher score (on an 18 point scale) is barely better than the 0.35 point difference seen for aduhelm. Still around 20% of participants had brain edema on imaging (although less were reported to be symptomatic).

In both cases we have benefits that are below the marginally clinically significant threshold over 18 months of therapy.

I don’t think we can write this drug off entirely with just a press release and 18 months of therapy, but this hardly sounds like a “breakthrough”.

Casava Science Phase III trials, promising with no side effects