ChatGPT Can Replace Dr. Google, But It Shouldn't Be Your Physician

This physician, for one, considers himself irreplaceable.

AI, LLM, ChatGPT, GPT-4… the acronyms of the Artificial Intelligence world flooded the realm of medicine these past two weeks. Yes, everyone everywhere is talking about AI, but when doctors — who normally pay little attention to anything of interest to the lay public — begin to get excited, I know something is afoot. That something seems to be a sense that AI is coming for our jobs.

The staid New England Journal of Medicine, a reliable late-adopter, is starting its own AI journal, for decency’s sake. It’s all-AI, all the time!

Now, contrarian observers might be thinking that when the NEJM gets into something, it’s time to sell. However, I think it’s almost an inevitability that AI will increasingly worm its way into the practice of medicine. In some ways, the movement will be a boon for patients. In others, it might prove to be a disappointment, or perhaps far worse. In any case, the conversation in health care is getting caught up in the fervor of the incredible efficiency which AI might bring to medicine, and, on the flip side, the obvious concerns about data security and automation. I think there’s more to discuss, though. Yes, before too long your doctor might be a computer, and perhaps even a full-on robot; it’s worth a good think, though, if that’s really the direction we want to head.

The Good

I’m not a wet blanket about the potential benefits of AI in medicine. I’m impressed with what I’ve seen the past couple weeks, observing what GPT-4 pops out in response to queries both obscure (“Does the genotype of Hereditary Alpha Tryptasemia affect the phenotype?” and commonplace (“Has any treatment for post-viral cough been proven effective by randomized controlled trial?”). It generally crushes me with the quality of its answers, to be sure, and I fancy myself a rather competent physician.

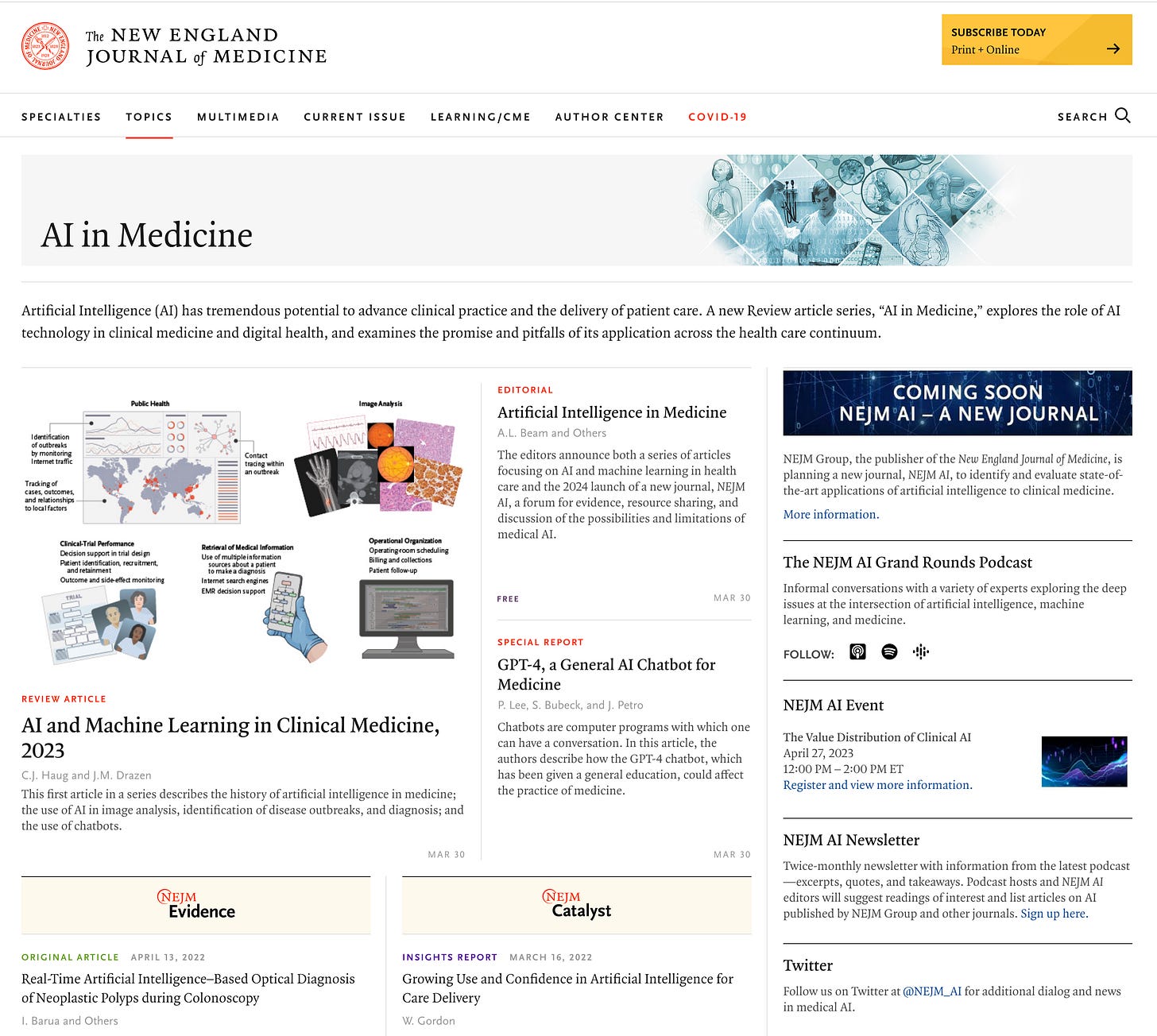

A recent NEJM article reviewed many of the ways medicine is likely to adopt AI. In citing the example of its ability to reason through a medical board test question, we see how well Chat-GPT can perform:

Now, I think most physicians would, like me, read this question and think, “Oh, this is that post-strep kidney problem;” but most of us who are not nephrologists might not remember that C3 levels would be abnormal in this setting. Chat-GPT acquits itself quite well in working through the problem logically — far better than I did.

Physicians are asked to remember and apply an absurd amount of knowledge. The internet has greatly reduced the need for a remarkable memory. Even the current iteration of GPT-4, despite not being specifically trained on medical cases, marks a huge upgrade in this regard. Information is not only rapidly gathered, but curated, as well. Ask about C3 levels in post-streptococcal conditions and you won’t just get a long list of studies, many of them esoteric, which may or may not answer the question at hand; you can request practical information, condensed and delivered in an instant.

This quality is also a great win for patients — and their doctors, therefore, too. Many of us have spent a good bit of time hand-holding the anxious patient who googled “fever for 4 days with skin rash” and came to the office convinced of their child’s leukemia diagnosis. Once patients relinquish “Dr. Google” for “Dr. ChatGPT",” they will get much, much better free medical advice.

So, yes, this technology is already poised to do a great deal of good in medical practice. It is virtually plug-and-play ready to serve as a backstop for clinical decision-making; to fill in the holes of any physician’s knowledge base in interpreting a lab test or imaging report; to write a chart note that is actually comprehensible while billing the right ICD-10 codes, simultaneously freeing up a doctor to have an extra five minutes with each patient; to coach us if we might have missed something important in a patient’s presentation. All good things!

Some of this goodness will come at a cost to our profession, but a savings to our system. Do you have a child in medical school competing viciously for a prized spot in a Dermatology or Radiology residency program, or a less-prized spot as a Pathologist? For God’s sake, tell them to match in a specialty that will still exist in five years! Those medical fields that are almost entirely pattern-recognition are at a grave threat of extinction.

The rest of us? Well, we tell ourselves that the “art of medicine” is still king. I’m not sure that argument will hold up over the coming years (maybe months!) — I suspect the next iteration or two of ChatGPT is likely to out-compete me as a clinician in almost every way, even when it comes to nuanced decision making.

That said, I still don’t think your next doctor should be a robot. Allow me to explain.

Garbage In, Garbage Out

Some things in medicine really can be competently managed by an algorithm. Choosing meds for high blood pressure, for instance, can be done as well or better by computer than physician, even if some nuance might be lost along the way (“Does she really take her meds?” “Is it time to double the lisinopril dose, or recommend a counselor to help with the stress over his step-son?”). Sometimes, though, it takes experience and judgment to wade through the conflicting recommendations of expert bodies, or decide which studies are reliable enough to update clinical recommendations before they are hashed out in formal guidelines years later.

The Covid-19 pandemic provides glimpses into this. The CDC made some asinine recommendations; would GPT-4 be able to sort out that in no universe could risk:benefit favor a healthy adult getting a second Pfizer shot if they had developed myocarditis from the first, or a twice-vaccinated male college student who had already gotten two mild cases of Covid receiving a booster shot? We can’t know since the training period for GPT-4 ended in September, 2021, and it will not wade in on such questions, but I worry. Ditto the use of Paxlovid in moderate-risk patients; most agencies push it, most savvy observers dispute it, and our only high-quality study suggests no benefit. I would be impressed at an AI tool that could figure out the side of the savvy observer over the less-savvy conventional wisdom.

An example not constrained by GPT-4’s training window is a favorite pet peeve of mine in the management of diabetes. An old and mediocre class of drugs, the sulfonylureas, have become outdated due to their propensity to cause dangerous low sugars and weight gain (and also to not work all that well over time). From many conversations with endocrinologists, I feel confident saying that there is almost no situation in which they should be continued if a patient is moved onto insulin. However, some poorly-constructed official guidelines still exist which encourage this practice. Could GPT-4 see through the noise? Not quite:

This is part of what makes medicine so hard. Sometimes money talks louder than evidence. Other times, we fall in love with convention, or are too easily wooed by the latest shiny new device. Genuine experts often disagree. Sometimes, however, thoughtful review of the evidence reveals that one side is clearly right! I acknowledge that anything I can figure out with my gorilla-brain can eventually be figured out, and then some, by a well-trained AI. However, we’re not there yet.

Reading the Room

Whatever constitutes “the art of medicine,” some of it is tuning into your patients’ unspoken cues. Most medical students are terrible at this; many of us become competent over time in this regard, however, with the help of repeated mistakes and the occasional gifted mentor.

A classic example is the “toxic” child. This is not what it means on social media, but rather a truly sick pediatric patient, one needing emergent care. Most infants and toddlers, crying from their headache and muscle pains with a 104℉ fever, will look pretty rough. Almost all of them can go home with their parents after some counseling. Every now and then, though, a child is just not acting right. The same 14 month old who was wailing with horror when you tried to examine them at their well-child visit a couple weeks ago, now calmly sitting in their mother’s lap with slightly glassy eyes and tolerating your stethoscope with nary a peep? Time to get worried!

Will a very capable computer figure out how the same behavior that could pass for “normal” with some patients in some settings is actually a red flag for serious illness in other contexts? Maybe. This strikes me as something that falls in the “not really playing to AI’s strengths” category — at least for now.

The Human Touch

To drop into the obvious for a moment: it’s nice to have another human being care for you. Now, when that human being is exhausted, running late, trying to compress an entire visit, chart note, and sick letter into fifteen minutes, and has 2500 other patients, you might not be getting a lot of that “care.” That’s a serious systems problem afflicting how we practice medicine in this country. Still — I think that even a disappointing encounter with a human is better than a leisurely conversation with a robot, in terms of its healing potential.

I know some people are fine interacting with non-sentient beings; some, it seems, even prefer a computer being to an actual boyfriend or girlfriend. However, a robotic doctor? That’s unlikely to be a therapeutic milieu. Since many studies have intimated that a doctor’s belief in the quality of the treatment they dispense — even when a placebo — will affect outcomes, it’s fair to extrapolate that having a human treating your ailments might be inherently healing. As community dwellers, we humans are also used to making agreements with other people, including agreements about managing our own health, and most of us have an innate desire to keep our end of the deal as part of our societal contracts. I don’t feel this way towards customer service chat-bots.

Worst of all is to envision a robot informing you that your CT showed a cancerous tumor. Ugh. There is no velvet-voiced, sweet-as-ET droid I could ever imagine as acceptable for breaking bad news.

Trust and Security

The practice of medicine is nothing without trust. Every doctor has felt the sting of a dubious patient — it is painful, not to be trusted doing the thing that we devote our lives to trying to do well. We get used to being trusted; as one of my first family medicine preceptors laughingly told me when I commented how much his patients loved him, “Oh, I don’t take that personally — the ones that didn’t like me all left a long time ago.” I don’t like making mistakes in medicine, but they’re inevitable; I don’t care for being fired by a patient whose expectations I didn’t meet, but it happens; but for a patient not to trust that I am on their side, doing my imperfect best to serve their interests — that would be crippling.

So: how do we trust an AI robot to be working in our best interests? Can we have a long backstory with it, watch how it behaves at church or in the community, see whether it respects my elderly parents at the supermarket? Nope. Do we know that it will have the same (programmed) values today that it displayed yesterday? Negative. Does even its programmer know how it will behave as time passes and inputs accrue? Apparently not. What if its programmer actually wishes to weaken your health, sell your secrets, or influence you to spend money on certain medical products which enrich the programmer’s company or nation? Gulp.

For all my pea-brained limitations, my patients know exactly what to expect when I walk into the exam room. If I come in reeking of bourbon, or complaining about all the spiders crawling on my skin, they know to walk out and try to find me some help. It might not be so obvious with a computer.

Of course, on a personal level, such concerns are worrisome; on a societal level, they are terrifying.

To properly harness all the data that could train AI systems to be fully-actualized physicians, we will be told that all our medical information must be up in the cloud where it can be accessed. We will be assured that it will remain private. We will be promised that the fruits of knowledge, the cost savings, the suffering and death prevented, will be far more valuable than the risks of automating and integrating our entire health care systems.

There will be merit to these arguments. They’ll probably win the day, because Science. Government and Industry will agree that the tremendous upside of turning health care over to AI is worth the risks.

It just makes me nervous. It’s scary enough to imagine the bulls-eyes that AI-controlled energy, transportation, and financial systems will have painted over them for our adversaries; but whole health care systems, too? Hospitals that are reliant on AI-augmented nurses, doctors, and surgeons to function will also be attractive targets. Malware attacks on Electronic Health Records systems are bad enough now, but once those knowledgeable humans who care for patients are replaced to the maximum extent possible by highly efficient computerized systems, taking down those systems could make a whole country cry uncle in precious little time.

I generally try to avoid futurism, because the most reliable aspect of the future is that it probably won’t look like you think it will. (Sports betting teaches me this lesson on a regular basis.) However, much as I suspect high-end concierge practices soon enough will begin to proclaim their use of EHR systems that integrate AI technology as a selling point, within a matter of years a few terrible stories will emerge that will start to push them in the opposite direction. “My practice is unplugged” or “Paper charts only, like your grandfather’s doctor kept” will be the new head-turners.

I’m not sure this is a bad thing. Yes, the internet has been a godsend for medicine; it has democratized medical knowledge away from the medical center libraries and academic journals and put it in everyone’s hands, at a faster pace than ever before. However, there is no device capable of reasoning through complex medical problems less prone to hacking, malware, and corruption than the brain of a physician. No large scale attacks can be made on this form of intelligence. Yes, the occasional foolish doctor falls for some nonsense on Twitter, or decides to tailor their oncologic recommendations towards the companies who pay their lecture fees, but these are not system-crashers, and are easily enough discerned and discarded. Ironically enough, perhaps the only way to protect our hard-won, computer-fueled medical knowledge is to store it primarily in our brains.

The heat of the excitement as one AI medical breakthrough after another is announced will have a shadow side in medicine. Once a computer can out-doctor an experienced physician, why keep pumping out physicians? It’s horribly inefficient, as well as expensive, to train doctors from scratch. If patients — the consumers of health care — don’t demand old-fashioned human doctors, with old-fashioned training, we risk losing a profession and an art which we might someday need to survive.

Everything I know was taught to me by tens of thousands of patient encounters, with a liberal sprinkling of didactic leaning and apprenticeship along the way. Much of that learning is stored, sometimes even in a format that can be rapidly retrieved! Always, though, it is available to help another soul, and always with the charge to “do no harm.”

It’s hard to replace that with a computer. Let’s not try.

I'd like for there to be a Dr Robot that was FREE, for things like "I've had an ear infection for 2 weeks now that seems to still be getting worse, and I really think it might be time to consider antibiotics" type stuff. For the uninsured working poor, that would just be an absolute godsend.

That would, in my utopia, free up resources to better pay human family physicians (and other MDs) for the more complicated stuff, where you really need hands, eyeballs, and a real organic brain to figure out how to best help the patient. The chatbot can be a wonderful *assistant to* a physician there.

I can't imagine that a Dr Robot would be good at working with patient preference when it comes to treatments, too. Having another human who knows more than you help you figure out what sort of plan of action is best FOR YOU can't be replaced. Side effects that are borderline intolerable for one patient are no big deal at all for another. I don't envision the chatbots understanding "I have X to do, and I HAVE to be in the sun to do it, or it's seriously going to mess up my quality of life" type issues.

I have very little confidence in physicians. They seem flawed, rushed and not that bright. That sounds bad, I know. Perhaps I'm projecting. I've long wanted AI to come into the field. I suspect that AI medicine will be heavily controlled by the same outside forces that control so much of what physicians do and say.