Cultural Sensitivity Is Getting in the Way of Stopping Monkeypox

Sorting through expert opinion on Monkeypox runs into some very 2022 problems

Monkeypox. My patients are asking about it, so I decided to educate myself about it, and share what I learned. What I found is that it’s probably not as mysterious as the media presents it. However, it’s no mystery why what’s likely going on is being soft-pedaled. It’s insensitive.

I am not going to provide a lot of background on monkeypox, as most everyone has already heard about it by now. There are fine threads on Twitter about its basics (a fairly severe orthopoxvirus endemic to several African nations, usually carried by rodents and passed on to humans in close contact), prior outbreaks (outside of Africa, historically limited to one country at a time), and contagiousness (not very). We have thoughtful videos, journal articles, and blogs for those interested in learning all about monkeypox.

The scary part, the part that keeps monkeypox in the headlines, is that so much is unknown. We don’t conclusively know whether something about the monkeypox virus or its human hosts changed to make it suddenly appear in so many places. (Though initial genomic sequencing suggests “the virus hasn’t mutated to become more transmissible”.) While we do have an old (rather brutal) vaccine in fair supply, and a newer (probably safer) vaccine in very limited supply, we lack much experience with how well they protect someone from an exposure. Ditto the available antivirals, which have far more animal data than human. So much uncertainty, and most of all, a lack of consensus as to what is really happening.

That’s what everyone really wants to know: “Why is monkeypox suddenly spreading in over a dozen countries, for the first time ever, and does this mean it’s going to sweep the world?” Expert opinion seems to break into two camps.

The “Everybody Should Be Concerned” crowd can be exemplified by the (very capable) Bill Hanage, here quoted in a Telegraph article:

Concerning. Then we have what appears to be the more widely held view, that this outbreak is limited in scope to those closely connected to the clusters of European sex-heavy gatherings which appear to have served as super-spreader events for monkeypox. We might call this the “MSM” camp, where we refer not to “main stream media,” but rather “men who have sex with men.” Here is World Health Organization’s Dr David Heymann:

Speaking to the BBC, the ECDC’s Dr. Andrea Ammon struck a similar tone:

What are we to believe when the experts disagree? While I have my doubts, the “Everybody Should be Concerned” camp does have its points. Not all the dots connect our initial cases to that 80,000 strong Gay Pride gathering in the Canary Islands or the Madrid sauna serving as MSM hotspot. The traveler from Nigeria who was the UK’s first diagnosed case of monkeypox has not been connected to either, as well.

Theories abound as to why we might have had months of quiet community transmission before the outbreak was ignited by a super-spreader event. We might have crossed a tipping point in immunity that enabled random chance to take over, with the steady proportional decay of people with cross-immunity to monkeypox from their pre-1970s smallpox vaccine.

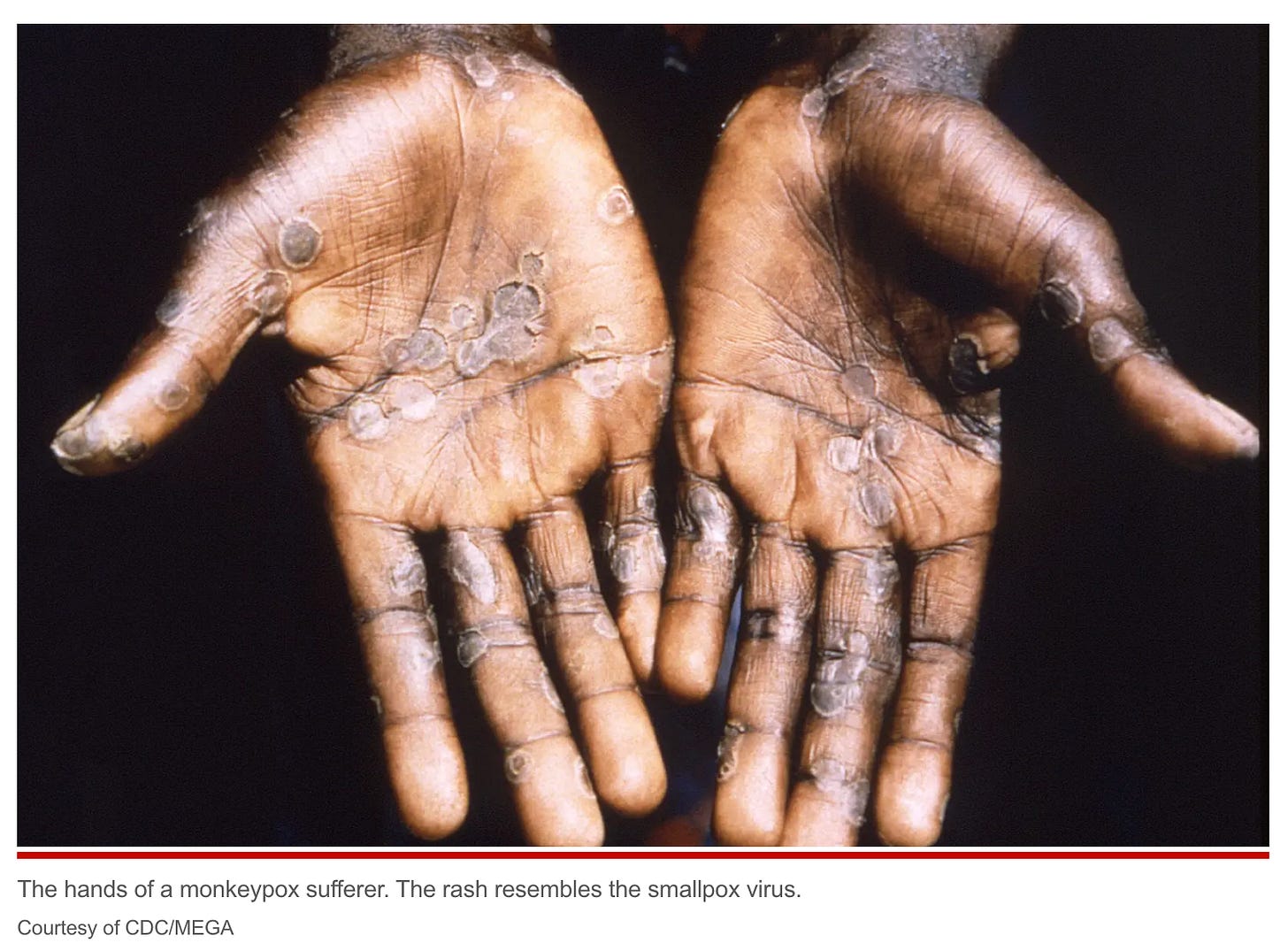

All this strikes me as possible, just not likely. Largely for one reason: we doctors might be fools, but we’re pretty good at pattern recognition. Pictured below is a pattern that would lead to a quick call to a dermatologist, infectious disease specialist, or the local public health department, because that is not your grandmother’s childhood chicken pox:

Unless the monkeypox virus mutated into a frequently un-pox-like form — and it does not appear the composition of the strains isolated from the current outbreak differ much from those of prior outbreaks — I struggle to believe this has been simmering for a while. Certainly, by now, all those missed cases would have the CDC’s phones ringing off the hook with calls from doctors who would now be second-guessing their shaky shingles and hand, foot, and mouth disease diagnoses.

There’s also the striking pattern of a high proportion of our known cases being youngish men, many who have sex with other men, and with travel histories not from endemic regions in Africa, but places like Spain. These dots are hard not to connect.

The first U.S. case in Massachusetts had visited Canada; a Canadian case had visited Belgium; and the Belgian case had been to Portugal, which sits next to the Spanish epicenter, per this European CDC report:

Since the warning first went out in relation to these large, MSM gatherings, it’s reasonable to claim that we might only be looking in the places where MSM go, like Sexually Transmitted Infection clinics frequented by the gay community, so we create a self-fulfilling prophecy of finding mostly gay male cases. I can’t buy this argument, though. Everyone has been looking for monkeypox for a solid week, and the remarkable lack of female cases and people without travel histories is striking.

I side with Dr Heymann; I think the balance of evidence and opinion favors his “single introduction” view. I question the more worrisome perspective that there were distinct introductions from Africa into multiple European and American nations, and community spread carrying on in several places at once.

That’s not to say we don’t have a problem on our hands. Just not so big a problem, as it seems more likely that monkeypox happened to be in the right place at the right time to trigger an outbreak, rather than some new threat to the world that it never posed before.

While the connection to MSM events has led a few to characterize “this” monkeypox as sexually transmitted, the prevailing point of view is that, like all monkeypox strains, close contact invites spread, whether via large respiratory droplets, bodily secretions like saliva, or the fluid within the rash blisters. Sex obviously falls in the “close contact” category. To a lesser degree, so, too, does being someone’s roommate or family member.

Interestingly, in the last major American outbreak of monkeypox in 2003, in which a pet retailer amazingly thought it was a good idea to keep Ghanaian rodents in close proximity to prairie dogs, and then sell the latter as household pets (okay, that’s a whole lot of bad ideas going on all at once there), none of the 47 human cases transmitted monkeypox to anyone else. Maybe people who think prairie dogs make great pets tend not to have a lot of close contacts, but that’s a remarkable lack of transmission. Also interesting is that 31% of cases ended up in the hospital in contrast to the low rates currently being reported. It’s possible that repeat handling of an infected prairie dog leads to a slightly different infection than sexual contact with a human being; but I’ll leave this stuff to the experts (and late show monologue writers).

In any case, anyone can get monkeypox, but in May of 2022, you were much more likely to get monkeypox if you were a man sleeping with men. This raw fact, coupled with the disease being endemic in Africa, leads to some ugly stereotyping in private, and overly gentle medical reporting in public.

Now, I know I promised a primer without cultural sensitivity, but that was pertaining to the factual part. The truth is, I am culturally sensitive, and don’t like seeing any group being ridiculed, abused, or stigmatized based on their choices. Anyone willing to challenge their preconceptions around the “hypersexual gay men” narrative evoked by tales of gay saunas and a Gay Pride sexual free-for-all might benefit from reading a post like this.

Medicine, though, demands brutal honesty. Right now is a really bad time for sex parties of any sort, especially in the gay and bisexual community. Men who have sex with men should be extra respectful of their close contacts for a couple weeks if they might have been within one or two degrees of separation of the gatherings in Europe that kicked off the monkeypox epidemic.

It has to be okay to say this. An essential part of medicine is having discourse with patients that discourages behaviors that risk disease or erode health. Some people love to drink to excess, or feast on fast food, or chain smoke Camels. We call out these behaviors (ideally in non-judgmental, collaborative ways that actually work). Promiscuous sex, on the part of heterosexuals, homosexuals, transexuals, or anyone, was never a public health winner: not in the era of HIV nor Covid; not long ago, given syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, etc.; and certainly not right now during a growing monkeypox outbreak. I don’t have an ounce of moralism on this subject — this is just medical reality.

I get the feeling that the Main Stream Media camp is a bit constrained in expressing this reality, for fear of offending an oft-harassed demographic. We are pointed towards very thoughtful warnings to avoid stigmatizing men who have sex with men, like this piece from The Conversation:

I agree — had the trigger been a St Patrick’s Day bar crawl, and the Irish-American community a hotspot for monkeypox, the societal response would have been different. But the correct advice would be the same: if you participated in the event, or share close quarters with someone who did, please take a couple weeks off from intimate activity with others until you know you are not beset with muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes, and a rash that makes you wish you had stayed home in the first place.

This is the public health message that should be going out in the MSM community. Instead, we have press statements like this coming from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, ostensibly to protect the people they serve:

There is literally not a single sentence in their 7 paragraph statement to acknowledge that perhaps large gatherings involving promiscuous sex also currently jeopardize public health.

I might be old-fashioned. I might just be old. I do think it is possible, however, to communicate honestly and effectively without having to tiptoe around people’s feelings. If we can succeed in doing so, we might find ourselves talking about something other than monkeypox before long.

Is anyone going down the rabbit hole that a year ago, there was yet another table exercise introducting monkeypox to the populations of the world--and a year later, it's happened?

The problem with the author's conclusion is that he wants to ignore basic facts. A very small portion of western men are responsible for a large majority of diseases. This has nothing to do with culture and everything to do with behavior. Until doctors fess up to the natural dangers of these behaviors, outbreaks like this one will continue to occur. MSM behavior is by its nature high risk.