Merck’s $38M Spanish Wrist Slap Reminds Us Why Our Meds Are So Expensive

The legal system has to make it harder for Big Pharma to rip off consumers.

Big Pharma went and did it again. This time, it was Merck, not playing nice with a potential generic competitor for its NuvaRing vaginal birth control product.

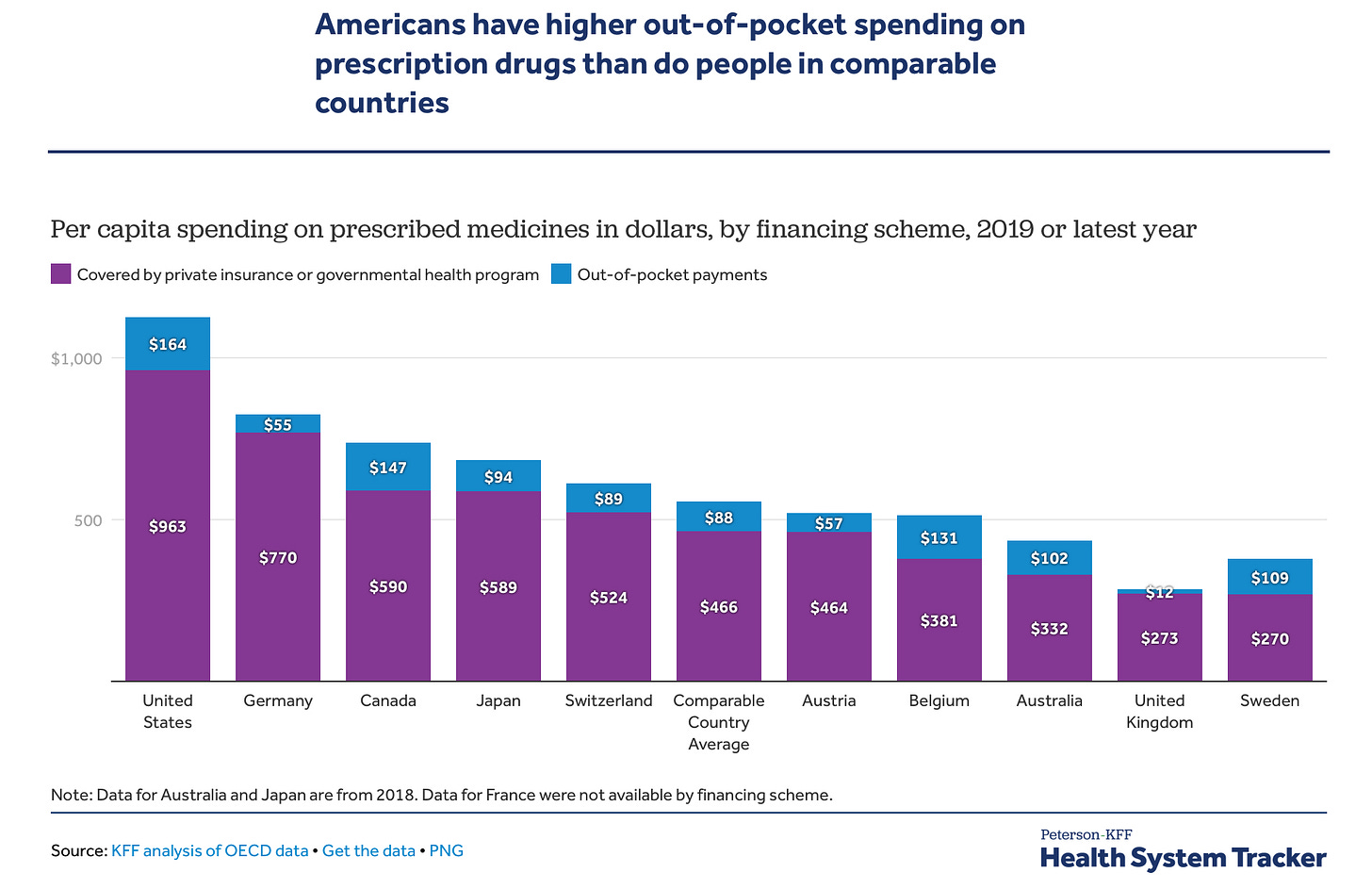

Why do we care? Well, the U.S. health care system wears the title belt for Most Expensive in the World, and some 15-20% of our health expenses rolls out from being proud owners of The Most Expensive Medicines in the World. In fact, per the Kaiser Family Foundation, we crush the competition!

If all your medications come off the Walmart $4/$10 list, you might not have noticed that we spend more than twice as much as citizens of our peer nations. Most of us have noticed, though. Some 80% of Americans think prescription drug prices are “unreasonable.” I am often astounded by the amount that my patients are asked to chip in as “co-pays” and “doughnut holes” for their monthly meds. There’s a lot feeding into the situation. However, the legal games being played by the pharmaceutical industry are a substantial part of the problem.

I don’t want to be overly dogmatic and pretend that the root of all pharmaceutical industry evil comes from its manipulation of patent law. Some of those high prices stem from our national aversion to having our government directly negotiate with pharmaceutical companies. This is going to change, for a few drugs, in a few years, in the realm of Medicare, with the passage of the cryptic Inflation Reduction Act. Allowing drug prices to remain totally opaque and settle where a scattered bunch of insurers are willing to set the market was never a recipe for low prices.

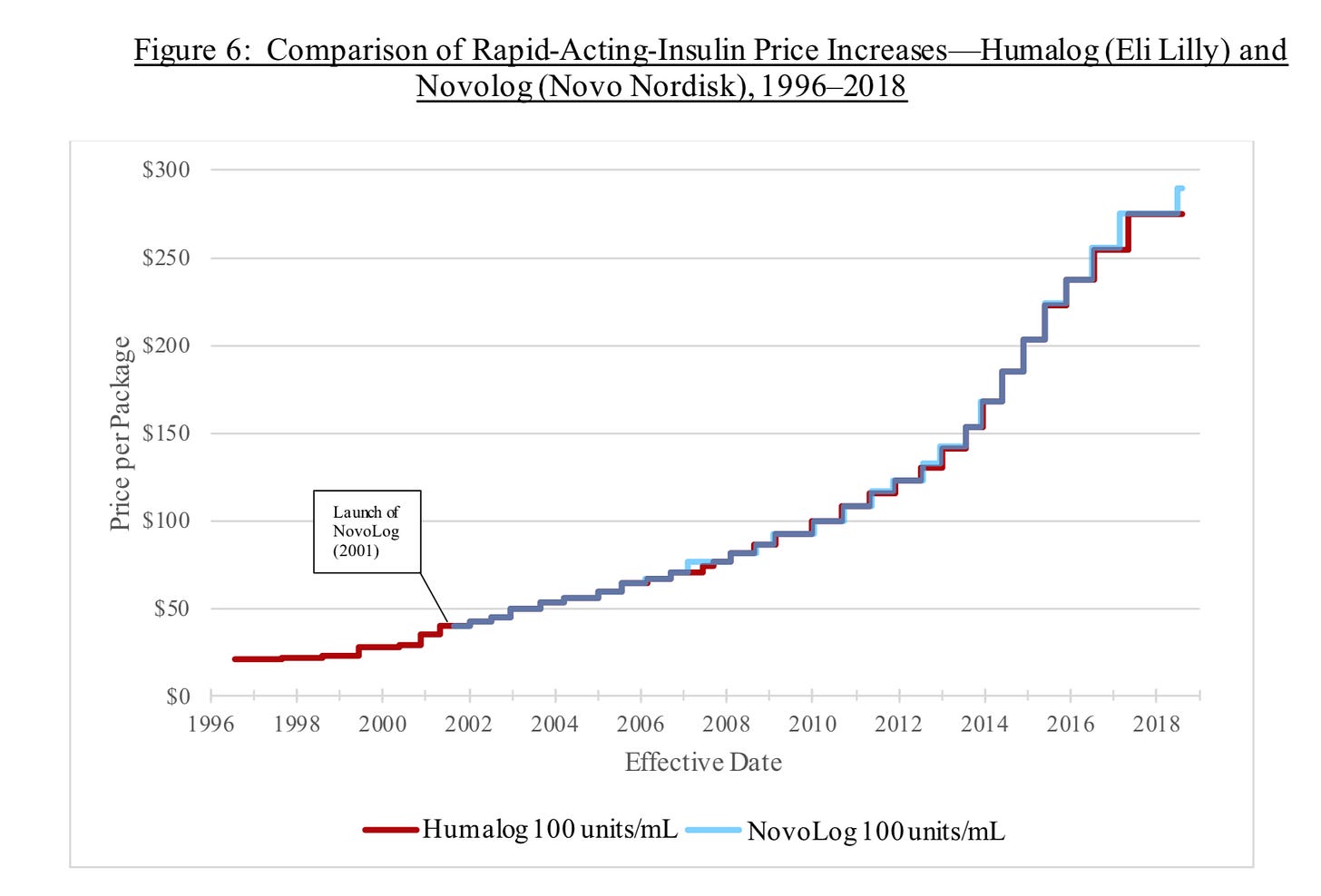

I must also note that while prices on most consumer items were stable until our recent global foray into inflation, pharmaceutical companies have shown a willingness to actively inflate their prices. The House Committee on Oversight and Reform released a 269 page report in December 2021 on the morass of Big Pharma’s profiteering practices. (I expect all of my readers to review it carefully, preferably emailing me a concise summary when done.) I can say that within the scope of a ten minute skim are some gems, like the lockstep rise in short-acting insulin prices between two ostensible competitors. It’s not a good look for believers in Adam Smith’s invisible hand; I think their CEOs instead favored invisible ink in their communications to each other around potential price hikes:

Now, to be fair, I have been reminded by a libertarian friend that I cherry-picked a prime example of how the pharmaceutical industry exists in a world of bureaucratic layers, barriers to entry, and opaque pricing practices, only some of which is of their own making. Part of why insulin costs so much is due to the grift of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (“PBMs”), and various state and federal price caps make anything like free market competition impossible. But those coordinated price hikes are symptomatic of a system untethered to the forces of competition. I happen to be a fan of free markets, and I even go so far as to align myself with that radical capitalist, Bono, in thinking that capitalism is probably the best option to solve most resource allocation problems. However, there has to be some sort of enforcement of common sense regulatory mechanisms to keep the graphs of some drug prices from looking like insulin’s two-tone staircase. That’s where the Merck Nuvaring case comes in.

Nuvaring, a useful if somewhat problematic addition to birth control offerings, was granted a U.S. patent in 1998 for the standard 20 years, and was approved by the FDA in 2001, leaving it 17 years to bring home Merck its bacon at the clip of $500M/yr. In 2017, Merck’s Nuvaring was the only vaginal contraceptive ring available in Spain, when a generic competitor, Insud, gained approval to bring its own version to the market. Merck successfully fought to challenge their right to do so based on violation of their patent in a Spanish court. It’s a garden variety medical patent case, meaning that: a) no one in the media bothered to describe the details because they are probably excruciatingly dull; and b) even if they had, I would not have understood them. I mean, this is a lawyer describing a prior case with Merck contesting Nuvaring’s patent rights against a potential generic, which they lost, and then won back:

Got it? Me neither. All lawyer speak is “nonobvious” to me. What was obvious to the Spanish authority, however, was that Merck had not been forthright in defending their patent claims.

Big Pharma likes to hide behind the obscurity of the patent process. The basic premise in granting patents, as well as periods of exclusivity in which no generic can be brought to market in certain conditions outside of patent protection (i.e., changing an existing short-acting blood pressure medication to a long-acting formulation can buy a company 3 years without a generic competitor), is to allow a company enough time without competition to earn back all the money sunk into research and development for that drug and all its cousins who failed. It’s the American way. The pharmaceutical industry likes to remind us how important this is. This bit of propaganda — I mean, explanation — from the premier industry lobbying group, PhRMA, says it all:

If you didn’t roll your eyes reading that, you may need a proper cranial nerve exam. I don’t shed a lot of tears of concern for Big Pharma. They’re doing okay. In fact, pharmaceutical firms are bringing in bigger profits on average than their corporate peers in the S&P 500. There might even be a little fat to trim off the bone; I note that Merck itself pays six executives north of $4,000,000 a year, three of them in the $10-15M range. Many have observed that the budgets for most pharmaceutical firms for research and development are exceeded by expenditures advertising and promoting their products (granted, that depends on how you view their accounting, and is a contested claim). Not contested is the sheer size of the Pharmaceutical lobby; almost $400M up in smoke in 2021 alone:

$400 million dollars, in one year, to influence policy to maximize profits. That’s a lot of beakers left in the warehouse!

I don’t blame a corporation for doing whatever it takes to please its shareholders. I do blame those of us who suffer from their pricing practices for not holding them accountable.

After all, it’s not just dollars and cents, which are plenty important to a health care system already teetering on the brink of financial viability; it’s access to important medications at stake, as well. A great example is Merck’s blockbuster drug, Keytruda (pembrolizumab). The Initiative for Medicines, Access, & Knowledge (I-MAK) breaks down the “patent wall” they built around this cancer drug; 129 patent applications, half of which were filed after it was approved to treat melanoma in 2014, and three-quarters of which were not even directly related to the essential antibody itself:

The bold section is probably most important. When the production process itself gains patent protection, it can be very hard for generics, even approved generics, to escape the courts without being swatted away for patent infringement. Merck’s $70B baby, which projects to be the largest grossing medication in the world within two years, will “fall off its patent cliff” in 2028, as they say in the industry. In theory, that should open up this extremely useful drug to be sold at lower rates than its current 6 figure annual cost, saving the system billions. In reality… I will believe it when I see it.

One cause for my cynicism is the wrangling that often ensues after a generic maker (and their generic lawyers) take on a highly profitable drug being made by a Big Pharma titan. If there is a patent lying around that could give grounds for contestation, the process moves out of the lab and into the courts. Guess who’s favored there? A common practice is for the patent-holder to sue the generic maker for patent infringement, which opens the door for a settlement. The terms typically involve a pay-off in which the generic agrees not to manufacture the medication for a period of years, if ever. Big Pharma gets to keep their profits. Generic gets a payday for nothing. Everyone wins! Okay, really — almost no one wins, and the patent system invites this sort of abuse.

That House Committee report cited example after example of pharmaceutical companies gaming the patent system by maintaining inappropriate patent controls or settling with would-be competitors to keep their generic off the shelves. I observe that report took them three years to compile. I think an industrious group of PhD students in Economics probably could have put together a report of similar quality in three months. I don’t want to put drug development in the hands of government. That’s terrifying. Keytruda is a great drug, and I’m glad Merck was motivated to develop it (or at least to pay a lot of cash to the people who developed it and then run the necessary trials).

I do think we can reform patent laws so that they serve both business and consumer. Yes, Big Pharma companies need to make money enough with their winners that they can cover their losers and be incentivized to stay in the business. They don’t have an existential need to take in excess profits to the point of lavishing spending on advertising as well as drop millions on lobbying efforts. As per this excellent Brookings report, most R&D spending actually goes into existing drug reformulation and patent extension rather than actively seeking new therapeutics. (Sadly, our fantasy vision of pharmaceutical research with brilliant people milling about a laboratory researching a cure for cancer just ain’t what usually happens in the world of pharma.) Again, I can steer clear of blaming Big Pharma for all their unsavory practices. Often they are simply rational actors, aiming to maximize profits like all successful corporations do, in an irrational system.

The system needs to be addressed, and I would vote for simplicity. Akin to these suggestions proposed for the EUS, I think the way out is by severely limiting secondary patents to avoid the worst of patent abuses; and developing fair time frames for exclusivity based on timing of the granting of patents and initiation of trials. A simple, transparent system — not the usual MO of lawyerly types, unfortunately — could curb the worst of abuses of the patent system.

When we perpetuate a patent system that tacitly encourages companies to protect their products from competition, we essentially allow them to create a monopoly for their product beyond what the granting of patents intended. Historically, we’ve also tended to look the other way when pharmaceutical companies act as oligopolies, our enforcement arms standing quietly by as competitors join a limited field and prices nary budge.

I watched as three very useful anticoagulants (brand names Pradaxa, Xarelto, and Eliquis) appeared from 2010 to 2015, fairly clear improvements over the old warfarin to prevent strokes in my patents with atrial fibrillation. Pradaxa opened with a price of $250/month without any competitors. Remarkably, with three in play by the late 2010s, they all cost within a few dollars of $400/mo, whether cash-pay from the local pharmacy or straight from my distributor. Now, finally with the emergence of a generic for Pradaxa as well as another branded competitor (Lixiana), prices are still up to $550/mo, although at least the generic is back to $400. That’s still a big copay for my patients without complete prescription coverage. I find it more than a little fishy that prices have essentially doubled in the 12 years since Pradaxa came out with a monopoly on the non-warfarin anticoagulant market, as multiple competitors came into the fold. That’s not how I remember my Econ 101 curves working.

Maybe there’s a more Pharma-friendly side to the story besides the patent litigation I read about every time a patient asked when these meds would be more affordable. I suppose it’s possible, if not probable. I can say that I hope last year’s $400M Department of Justice “bust” of three generic drug makers for price fixing will not be the last, and that it sends a message to those tempted to set prices above free market rates.

It’s well nigh time to stop giving Big Pharma the right to create monopolies for eons, and then to price-fix like oligopolies for the rest of time. I am not a fan of big government nor excessive regulation, but we have to accept that the pharmaceutical industry is not a natural field to fully turn over to the free market. With apologies to libertarians everywhere, we have to regulate it or we’ll get marginally effective products pushed at high costs to desperate consumers (and regulate smarter, as recent FDA approvals for expensive flops like molnupiravir and Aduhelm show). Regulation means limited competition. Protecting intellectual property rights means even less competition. There’s not much room to tolerate bad behavior from pharmaceutical firms attempting to avoid all competition.

I’m sure this is not what those who support a modest legislative solution to high drug prices want to hear, especially those optimistic enough to believe the provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act will suffice to control medication costs. First of all, I’m not sure anyone in or out of government fully comprehends what that plan sets out to accomplish; but it really only aims to help those with Medicare, and will hold down prices via direct negotiation for only a handful of Medicare medications without competitors. It’s not creating a more competitive playing field across the industry.

No, to really harness the free market to bring down drug prices, we need to change our patent laws and how we enforce them. The pharmaceutical industry and their massive lobby won’t like it, but if forced to choose between playing fair and having the government set all their prices in the setting of a socialized, single payer system, I think they’ll see the light.

I’ll leave it to the lawyers and politicians to sort out the details. Those, at least, are two groups of people we can all trust.

Just wanted to say thanks for writing this piece, Doc. I've shared it with a few friends - also insulin dependent - and it's really, really heartening to have an MD weigh in on this unjust morass, when so many are content to just stay the fuck out of it. Bravo, and thanks again.

You fail to consider foreign markets. Many countries have price controls which make it impossible for the drug maker to make any money there. Instead of refusing to supply the drug, they make up the loss where there are no price controls. We are subsidizing foreign consumers.