Like many aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic, your feelings about “long COVID” might be flavored by your political leanings. Fed up with public health officials influencing where you can go, what you can do, and whether or not you have to cover your face with a mask? Then long COVID could be seen as a fantasy of the worried well, whose “brain fog” and fatigue probably existed before that Covid-19 infection they may or may not have actually experienced. Think the White House and CDC are failing us by ending vaccine mandates, dropping indoor mask requirements, and talking about “learning to live with Covid” instead of eliminating it? Then long COVID is debilitating, affects some 10-30% of everyone who gets Covid, and, now that Covid patients no longer overrun the hospitals, arguably is the most fearsome aspect of the disease.

Most likely, the reality is not somewhere in the middle — but rather that both camps have it completely wrong. Long COVID is real, and can be a truly serious problem. It’s probably rare, though, which is about the only positive thing I can say about it. I don’t have many answers for the problem of long COVID, but I do see that the popular conversation on the subject has left most people — including many physicians — confused.

To begin with, we don’t even have a proper definition for long COVID. The CDC is vague in describing long COVID as a set of symptoms that “last more than 4 weeks” after infection; but does provide a long list of potential symptoms:

The WHO takes a slightly different and more concise tack:

Both definitions fail to provide clinicians with much of an idea of what to expect when they actually see a patient with long COVID. The vague language and broad list of possible symptoms also provide fodder for those who like poking holes in the very notion that long COVID exists.

As to the term, “long COVID,” there is not even agreement on a name; some prefer the more medical-sounding post-acute COVID-19 or post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (“PASC”). I’ll say that trying to settle on a single name misses an essential point as to the nature of the disease: it’s not one entity. More on that later.

First, though, the numbers. While the rates of long COVID quoted in the media from The Experts vary a bit, 10-30% seems to be the most commonly cited figure. Here, the American Medical Association making this claim:

This is a rather terrifying assertion! I mean, 10-30% is very much a “not rare” proportion, especially after mentioning “mild” infections. I don’t think this is healthy reading material for the American public. In fact, I’m not generally much of a hypochondriac, but when I started having some recurrent facial muscle twitches 3 days into my recent bout with Covid, my honest first thought was, “Oh, no, it’s long COVID muscle fasciculations, and they’re never going to stop.” Seriously.

If we roll with these estimates, we can land with some pretty striking numbers. Here, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation maintains a dashboard based on these theoretical percentages (the dashboard uses that 30% number as its default):

26 million Americans suffering with long COVID!

The Washington Post went in heavy for this approach:

Of course, there is one obvious problem with these figures: they make no sense. Everyone knows scores, if not hundreds, of people who got Covid by now; does that mean everyone knows ten or twenty people with real-deal long COVID? On the contrary, I’d say the only people knowing that many people with long COVID work in long COVID clinics. These are the same people who are asked to give radio interviews, join podcasts, and discuss long COVID with the media. It’s a distorted view.

I’ve had a couple hundred patients get Covid (I have a small clinic; most doctors would have thousands). Total number with anything like what I consider a serious, post-Covid illness? Zero — although a couple are teetering a bit. I decided to run this question by several colleagues; “how many patients on your panel do you have with over a month of ongoing post-Covid health issues serious enough to seek care with you?” The answers ranged from “none” to “a few” to “maybe a dozen” — but true long COVID cases always fell well under 1% of their total Covid cases.

I won’t pretend this is real science; but it does match what we see out in public, any time we can define a denominator. Congress? About 200 have claimed Covid infections, but only one, Senator Tim Kaine, has publicly described a case of long COVID. The two thousand-plus closely-scrutinized athletes in the NFL, NBA and MLB, most of whom have gotten Covid by now? I could only find four reports of limitations from long-COVID to this point. Where are those 30% hiding?

The reality is that they never existed.

Nature recently published an article pondering why it’s been so hard to pin down a reasonable prevalence for long COVID:

Lacking a shared definition, every study is free to define long COVID as they wish; in the widely-published ZOE UK data, based on volunteers submitting data through a phone app, a participant was added to the long COVID totals if they had one or more new or ongoing symptoms 4 weeks after a Covid infection. That’s a low bar for a case of long COVID! More problematically, the sort of person willing to join a study of this sort, and regularly input data via a phone app, is probably the sort of person with a particular interest in long COVID; perhaps because they are particularly worried they are destined to get it.

On the other hand, many studies rely on Electronic Health Record data to look for the rate of new diagnoses among patients in the weeks after they register a positive PCR. Aside from concerns with how fraught it is to rely on my colleagues to code diagnoses in a sensible manner (coding is on every physician’s “least favorite tasks” list), the greater problem is that, compared to someone who doesn’t bother to be tested, or runs a rapid test at home to get their Covid diagnosis, the average person who seeks medical care in order to obtain a PCR test is probably more likely to seek medical care for some other, possibly unrelated, medical problem, a month or two later, and bring a hit to a “long COVID” database search.

Really, though, most problematic of all is that the great majority of the scores of studies done on long COVID prevalence have failed to include a control group. I don’t blame them; it’s awkward to ask a bunch of people who had nothing happen to them whether they feel ill.

When a long COVID study does include a control cohort, the numbers tend to be more modest. Examples include Marc Lipsitch et. al.’s clever 2021 work utilizing EHR data which found only a 1.65% increase in new complaints 3 or more weeks after Covid infection versus a pre-2020 comparison group of patients who had been diagnosed with a respiratory virus; and this week’s JAMA study on long COVID in children, which surveyed children after ER discharge or hospitalization with a Covid diagnosis, and found a 1.6% increase in the rate of new or persistent symptoms in the non-hospitalized (but still sick enough to go the ER!) group 3 months after infection compared to a cohort who had not been infected.

I don’t want to imply that I think 1.6% is our magic number because it popped up in both studies. Of note, both these studies were in the first year of the pandemic, and might well have picked up a higher rate of persistent COVID from sicker patients than we would see today with Omicron. I also doubt they represent the odds for a “typical” person infected by Covid, who might be more averse to entering the medical system than those studied. I still think the “eye test,” unscientific as that may be, suggests the meaningful rate of long COVID to be lower, if we define it as I would, which would be: the incident rate of 2 or more months of persistent post-Covid symptoms disruptive enough to affect quality of life or the ability to work, beyond the amount of new chronic complaints that would happen to people living their lives pre-pandemic.

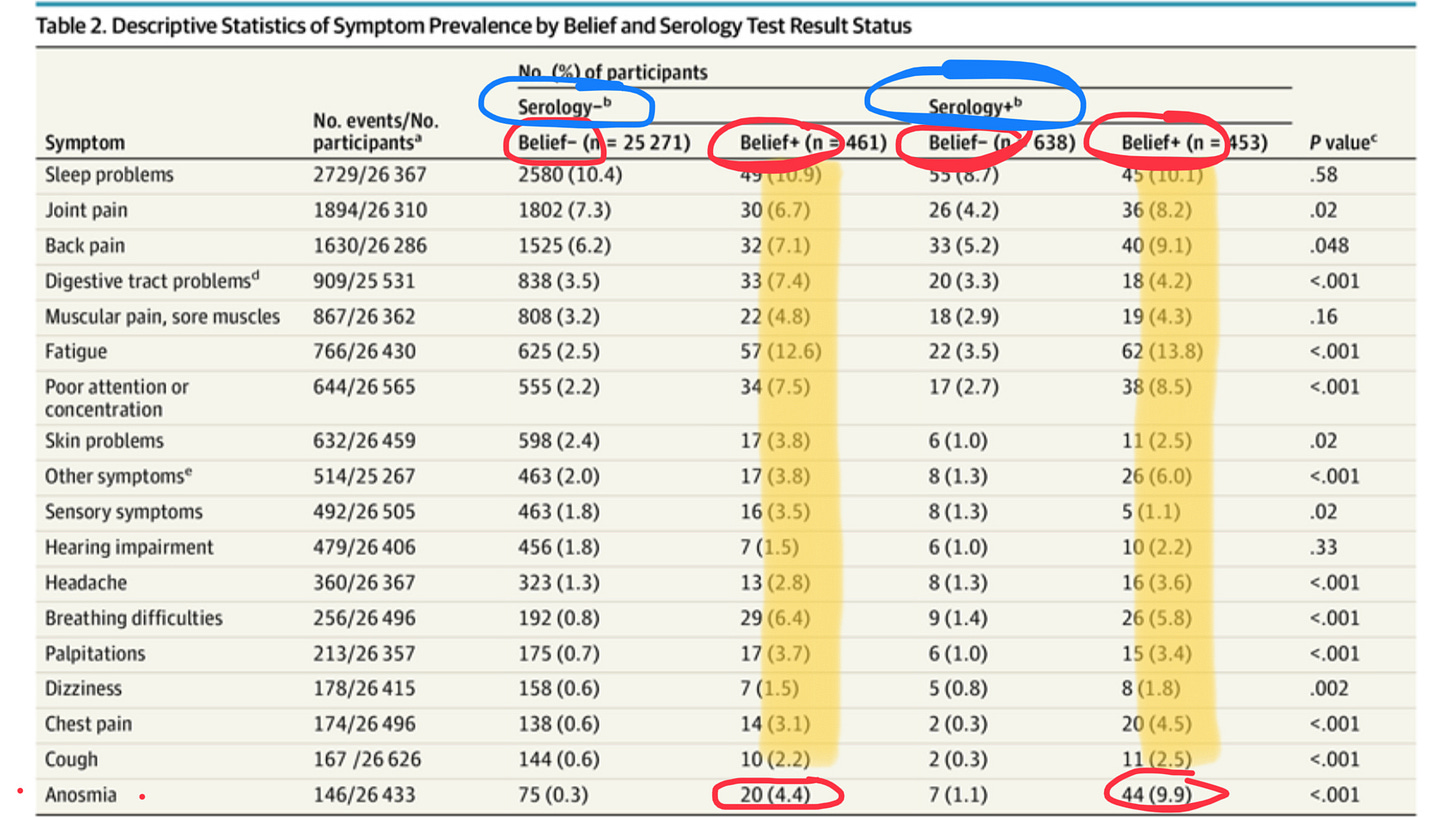

One of the splashiest studies including a control group hailed from France, published in JAMA, that had a rather clever control cohort: people who thought they’d had Covid, but actually tested negative on blood serology (note: of course, some of these people were just false negatives due to waning antibodies, but the authors do try to account for this). The best predictor of whether someone reported long COVID symptoms was not whether they actually had antibodies as evidence of prior infection, but whether they thought they’d had Covid. The lone exception was loss of smell (anosmia); for this particularly “hard” finding, actually having evidence of a Covid infection increased the odds of having this persistent complaint.

This study led to some predictable takes from some predictable pundits:

Unfortunately, Alex Berenson was wrong (this is a sentence I have broken out more than a few times during the pandemic).

Long COVID is real. It’s rare enough and sufficiently amorphous to be hard to capture in a study that includes a proper control group. I could dream up a study that could actually give us something like an accurate estimate of long COVID rates, but it would need to be prospective (i.e., starting now), and involve a medical professional asking a lot of people a lot of questions over a long time period. It ain’t gonna happen. So we’re stuck ballparking numbers; just please not the absurd numbers currently being peddled. They distract from the very real problem we have.

So, why all the trouble agreeing about what constitutes long COVID? Part of the problem is that it is probably at least two distinct entities: the one most of us envision is really a sort of “long-tail COVID”, afflicting generally older, often male, patients, who got very ill with their Covid infection and took months to recover. This is probably related to tissue injury/inflammation from a severe infection; i.e., that colleague-of-a-colleague of mine who went from marathon runner to struggling to walk across the room for many months after his bad case of the Wuhan strain. This, however, is but one form of long COVID. David Putrino, a physical therapist at Mt Sinai involved in studies on rehabilitation of long COVID patients, does a fantastic job explaining this concept on an In the Bubble podcast with Akiko Iwasaki (worth a listen if you can handle Andy Slavitt’s incessant ad recitations).

When doctors say things like, “since the risk of long COVID is associated with the severity of the infection, we expect Omicron to cause long COVID at a lower rate,” this sort of delayed recovery from an infectious insult is what they’re thinking about. Fixating on “long-tail COVID” is probably a mistake, however. Given the remarkably low rate at which the current Omicron sub-variants seem to be putting people in the hospital despite an incredibly high plateau of cases, and reports of ICU-level Covid pneumonia dropping towards zero, I think “long-tail COVID” will increasingly be a dinosaur.

The version of the disease that has been filling the dozens of clinics that have popped up to serve long COVID patients — and now have long wait lists — appears to be a different beast. It skews younger and female. It’s something that makes physicians uncomfortable; to borrow from Alex Berenson’s lexicon, a set of “squishy” symptoms that don’t fit well with what we were taught about in med school. Brain fog? Tingling skin? Temperature dysregulation? Lightheadedness? Fluctuating fatigue? These are nightmare complaints for doctors, and not just their patients. Usually no lab test, no exam finding, will bear out what the patient is describing.

Listening to David Putrino describe his patients — or Dr Kathleen Bell, or Dr Svetlana Blitshteyn — it’s apparent that those working with long COVID patients now are largely dealing with people whose nervous systems are failing them. Some are plagued by headaches or cognitive issues. Fatigue — not so much shortness of breath or muscle weakness — is a common complaint. Many are beset by their own autonomic nervous system; the elegant execution of the sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) nervous systems becomes scrambled, and strange problems result, ranging from Senator Keane’s crawling skin and zapping nerve sensations, to heart rates jumping from 60 to 150 to 60 again without provocation, to odd episodes of lightheadedness while standing. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction, or dysautonomia, is a seriously disruptive health problem, but it’s so recently and reluctantly recognized that I received about 5 minutes of education on the subject in medical school and residency combined.

If you walk into the office of a typical medical doctor and complain of brain fog and light-headedness ever since you got Covid, you might be greeted with an empty stare and ill-conceived lying-and-standing blood pressure tests (normal, of course) that will lead to the suggestion to add some salt to your diet and stay hydrated. This is not what we do well in “modern medicine.”

It’s also not what we handle well as a society. We tend to understand if someone blows out their back in a car accident, horrific MRI and spinal fusion hardware as proof, that they might not be able to return to their job. Brain fog, fatigue, and a racing heart? Suck it up and get back to work.

I was saddled with a few days of what I would describe as brain fog about a week into my Covid infection. It was a strange sensation, like someone had packed cotton wool around my brain; and trying to access thoughts, facts, or feelings had this depressingly unpleasant and difficult air. I can’t imagine having to go work in an Amazon warehouse, a call center, or even my friendly clinic’s front desk, feeling like that. I say this as someone who has literally never missed a day of work in my life due to illness, and with full awareness that my brief foray into post-covid symptoms was about a 2 out of 10 on the severity scale of what genuine long COVID patients are trying to manage.

So, where do we go from here? The current plan seems to involve throwing a good deal of money at the problem. I’m not sure where that will take us.

Perhaps we’ll get a handle on what causes long COVID. While multiple theories abound, I suspect ultimately we’ll figure out that long COVID sufferers either have twitchy immune systems that SARS-CoV-2 is better at switching to a “stuck on” position than most pathogens; or that SARS-CoV-2 is better than most pathogens at hiding out in people vulnerable to long COVID, perhaps in their gut and/or lymphatic tissue, and continually presenting bits of virus to the immune system. As to the theory that Covid infections trigger “microclots” that block up our blood flow all over our bodies, I find it a questionable match for explaining anything but “long-tail COVID” symptoms, and am always leery when a single investigator (in this case, Dr. Resia Pretorious in South Africa) spawns an entire theory which then creates a slightly sketchy cottage industry. Call me skeptical.

I happen to favor the overactive immune system theory for underlying long COVID, but will allow that some work has found persistent virus to correlate highly with the presence of long COVID. Either way, once the immune system gets stuck in inflammatory mode, strange and unpredictable medical problems commence.

We probably need to sort out what causes long COVID — with an awareness that it might well be different causes in different people — before we can figure out how to treat it. If it’s autoimmune in nature, steroids, histamine-blockers, and big-gun immune modulators might prove effective. If persistent virus is really the problem, vaccines and antivirals make more sense. Treating microclots means blood thinners. Given all the uncertainty, results from randomized controlled trials are desperately needed.

Whatever the cause, the dysautonomia crowd tends to be remarkably hard to treat; long COVID clinics offer an array of treatment modalities, from meds to physical therapy to lifestyle interventions, but insurance companies are not always anxious to pay for them. I was heartened to hear both Putrino and Dr Bell mention that about 60% of their patients improve over time with treatment; whether that’s mostly the time (since there is no placebo group at a long COVID clinic) or the treatment, I don’t know.

To be honest, I’m not terribly optimistic that we’ll find effective treatments for long COVID in the near future. As someone with a growing curiosity in the broad swath of controversial medical problems that most resemble long COVID — diseases like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Fibromyalgia, Mast Cell Activation Syndrome — I see that one common thread binds them together in terms of treatments: most fail. It’s made me more old-fashioned than ever in trying to help patients like this, but not everyone has the means or motivation to reconsider what they eat, how they work, where they live, and how they move, especially without any guarantee of success.

What does this all mean for the impact of long COVID on the world? I thought Ben Mazer’s Atlantic article did a nice job of expressing the contradiction between the bold claims of a highly theoretical mass disabling event, and the more modest problem that can be seen with our own eyes.

I hope his numbers are high, based as they are on studies which were not designed to accurately find the prevalence of the problem. I hope the rate of even mildly disabling (or “deteriorating”) long COVID matches the eye test, and really is well under 1% of infections. I hope “long” is measured in weeks, maybe months, for most people, and not years.

I hope all these things. But, still — I worry.

Having seen hundreds (if not thousands) of individuals with severe covid in the hospital, I have perhaps a different take. Early in the pandemic, up to 15% of COVID19 sufferers were admitted to hospitals. As therapies improved (steroids, then monoclonal antibodies), and outpatient oxygen became more available, that percentage certainly declined, though the hospitalization number increased wave-by-wave here in Tennessee. It declined further of course after vaccinations and/or prior infections became commonplace. That said, it was a huge number of people.

And *most* of them had persistent symptoms >4-6 weeks after their illness.

Viral pneumonia/ARDS wrecks the lungs. It leaves scars. (Severe cases of pneumonia from other pathogens do as well, of course)

Covid-19 wrecks the brain. The average person hospitalized with covid, according to UK researchers, loses 5-7 IQ points. If ICU, 10-15. I can’t count how many elderly patients I admitted in ‘20 who started with mild cognitive impairment, but were discharged with severe dementia.

Blood clots, myocarditis, acute liver or pancreatic injury; all of those acute manifestations may have long term consequences.

We had great success in improving outcomes throughout the pandemic. But there was a lot of trial and error on the way. Among survivors of covid-19 from 2020? *Way* more than 1% were physically damaged permanently. Maybe it was even as high as the lower bar 10% figure. There were certainly many more who never got admitted whose symptoms were severe enough to forbid work, and which persisted a long time. I know quite a few healthcare providers in that group. Maybe half again as many? An additional 5%? Like you, the 30% figure seems absurd to me too.

Even among 2020 survivors.

The covid experience is entirely different now, with a mostly-partially-immune population. <5% of covid cases get hospitalized now, and despite their typically advanced ages, they’re not nearly *as sick*. Considering that vastly more Americans got covid in ‘21 and ‘22, and the prevalence of long term injury dropped so greatly (I will not comment here upon my Southeast USA Delta variant experience last summer…), that 10-15% has been diluted out such that I’m sure long covid now is <5% of the total.

Regards.

I enjoy your blog!

I suspect we are dealing with 3 distinctly different populations. One may represent low grade persistent viremia. The next covid neurologic injury. The last is the group of patients that chronically do not feel well and are looking for a explanation whether it be chronic EB, chronic fatigue, total environmental allergies etc. Ultimately all we have to offer is supportive individualized management requiring deft clinical care which cannot occur if we try to put everyone in the same box. J. Burk Gossom MD