Should We Stop Pushing Statins?

A recent study questions their value

I freely admit this to my patients: I am a statin agnostic. It’s rather embarrassing. Statins have been around almost as long as Religion, undeniably lowering cholesterol levels the whole time, and yet I cannot quite make up my mind about them, despite all the studies and sales.

A recent meta-analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine led by Dr Paula Byrne re-stated the primary causes of my agnosticism: people with a low risk of a heart event are not very likely to benefit from a statin drug. True, it is almost universally accepted that people who have already suffered a heart attack or have other known cardiovascular disease substantially reduce their risk of another bad event with statin usage (so-called “secondary prevention”). But still controversial is what to do with the 25% or so of U.S. adults over 40 who don’t have a history of known heart disease but are currently recommended to take a statin (in the name of “primary prevention”).

In a nutshell: should healthy people with high cholesterol be put on statins?

The question is informative, both for patients and their doctors, as the basics of this quandary are statistical, but the complexity lies in our physiology.

First, though, the study. Not coming to us through the pharmaceutical industry, but rather multiple research centers, we might have reason to trust the authors’ intentions. I suppose it is worth noting that Dr Byrne has published a report to this effect before, so perhaps a small grain of salt should be taken with her conclusions. Sometimes we tend to find what we go looking for in science.

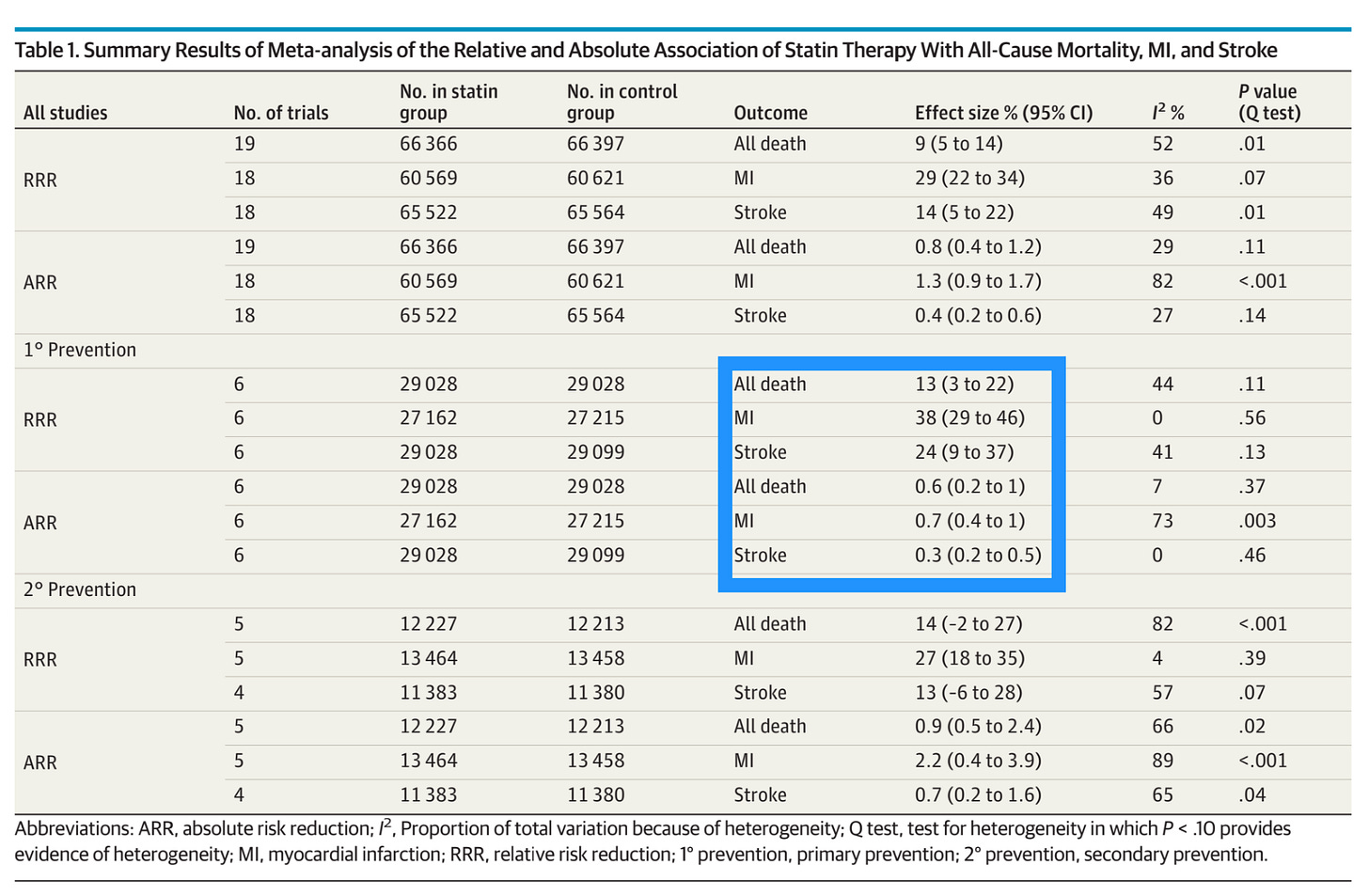

That said, there is little altogether shocking in the report’s findings. In 19 randomized, controlled trials, running over 2-6 years time, those on statins were 29% less likely to have a heart attack, 14% less likely to experience a stroke, and 9% less likely to die than their counterparts receiving a placebo. Science is uncertain how much of this effect is due to the cholesterol-lowering properties of statins (they block cholesterol production in the liver), and how much is due to some unique vascular anti-inflammatory or plaque-stabilizing effect, but whatever it is, those are some good numbers. Of the trials looking only at primary prevention, the numbers were even better, as per the box below:

Of course, statin drugs have earned their makers a pretty penny, maybe north of a trillion dollars; appropriately, the authors remind us that the studies they examined might not be without bias:

Still, unless we think the robber barons at Pfizer, Merck, and AstraZeneca have cooked the books in study after study, the numbers speak for themselves rather loudly. Take an inexpensive pill and lower your risk of a heart attack by almost 40% — a no-brainer, right? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

The author explains the notion of absolute risk reduction vs relative risk reduction nicely herself in a piece she wrote. Many in the lay public have become familiar with the importance of these terms over the course of the pandemic, but here is her refresher:

This is how I like to frame the discussion with my patients. 40% (relative risk) reduction in heart attacks sounds fabulous! 0.7% (absolute risk) reduction sounds… drab. It implies a need to treat 143 people in those primary prevention trials to prevent one heart attack.

Essentially, if I am seeing a healthy patient in their 40s with high cholesterol and a calculated 5% risk of heart attack over the next 10 years (risk calculators of this sort abound), I tell them that their risk might drop to 3% if they take a statin drug every day for the next ten years. For some people, that’s an easy sell. Others get that look in their eyes that tells me they’re figuring out that in 50 parallel lifetimes, only 1 of the 50 ends up dodging a heart attack by taking all those pills.

I fear this framing might be overly simplistic, however. All these studies are using a relatively short time horizon. I like to think of exposures — whether positive or negative — like a toxicologist, via the “Area Under the Curve” concept.

Whether it’s measuring happiness over one’s lifetime or the mercury in all that ahi sashimi I ate before I knew better, low doses for brief periods have a much smaller cumulative effect on one’s life and body than high doses for prolonged periods. Can this principle be applied to statins?

I don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows, since running a randomized, controlled, double blinded trial on statin drugs for 20 or 30 years falls in the “Ain’t Gonna Happen” category of science. I allow that statins might win in this scenario, however.

For one, we don’t understand the physiology of cholesterol plaques all that well. I mean, you can find nice pictures of them online and in text books, but everyone develops arterial plaques, and not everyone has a heart attack, or experiences symptoms like chest pain from angina or calf pains from peripheral arterial disease. What’s more, simply having plaques is not a great predictor of the risk of heart attack, or stroke; it’s the inherent instability of the plaques, their tendency to throw off an embolus that can lodge downstream and choke off a coronary or cerebral artery and cause a heart attack or stroke, that’s the real concern. Assessing this risk has been a cottage industry for decades, with blood tests like C-Reactive Protein and imaging such as Coronary Artery Calcium scoring, but there is anything but agreement as to whether these measures add much information over a basic cholesterol panel.

There is little doubt, however, that plaques accumulate as we age. There is also little doubt that interventions — whether dietary or medical — which lower cholesterol levels can also alter existing vascular plaques. It seems plausible that long-term cholesterol reduction might limit the development of potentially clinically relevant plaques in our arteries; and that waiting until older and higher risk might be coming too late to the party. A lot of things in medicine seem plausible, however, but are not true. I would like to see real evidence of this phenomenon before making it a foundation of my treatment plans.

Another point for starting primary prevention sooner rather than later is that the benefits of statins might proportionally increase over time. Some lipidologists propose, for instance, that LDL (“low density lipoprotein”) cholesterol, the so-called “bad cholesterol,” is inherently inflammatory. More time building bigger plaques with more of these inflammatory particles bouncing around the insides of our arteries could conceivably amount to a positive feedback cycle which would not be fully captured in a 2-6 year trial.

A friend sent me a response to the Byrne meta-analysis from longevity guru, Dr Peter Attia. He spends a lot more time thinking about statins and cholesterol than I do, and he (aside from revealing himself also to be a fan of Area Under the Curve thinking) did share the position that a 4-year trial is too short to really measure the effect of statin use.

I might just be dim, but still I struggle to be convinced that more time would yield more impressive risk reduction. An analysis Attia cites as evidence of this effect essentially melds statin trials for risk reduction onto (unrelated) real world data on cardiac events for people with genetic tendencies towards low cholesterol, to come up with a claimed three-fold improvement in heart events per given drop in cholesterol if cholesterol lowering is started early in life. Okay, I admit it: “Mendelian Randomization Analysis” is way out of my wheelhouse. But it doesn’t exactly satisfy my need to have actual randomized people followed over actual time with or without a given actual intervention. Call me old fashioned.

There’s one other problem with all this enthusiasm for cholesterol lowering. Are we really all that sure that “bad cholesterol” is all that bad? After all, evolution exhibits great parsimony. We need cholesterol or our livers would not dump it into our blood stream. It’s a vital component of our cell membranes, and a precursor for steroid hormones, bile acids, and vitamin D. A BMJ study from 2015 provided lasting fodder for the “LDL is good, not bad” crowd: for the most part, high LDL levels in people over 60 were associated with living longer.

Now, the potential for confounding screams out here (although the authors do attempt to address it). It’s frankly hard to reconcile this data with the sort of studies we have, akin to those utilized by our Mendelian modelers, in which people with genetically-determined low cholesterol tend to have fewer heart events, and with genetically-determined high cholesterol tend to have more heart events. It’s interesting, though, and cools my enthusiasm a bit for driving everyone’s LDL down through the basement.

Similarly, the value of using medications other than statins to lower LDL has had mixed results over the years in terms of outcomes. One of the conclusions of Dr Byrne’s meta-analysis was that the holy connection between the degree of LDL-lowering, even with statin use, and the degree of protection from vascular events might not be as strong as most commentators assume. Per the graphs below — yes, the lines all slope upwards, as the dogma would suggest; but you could sneak a pretty flat line in there within those confidence intervals, too.

Outside of statins, other LDL-lowering medications have a mixed track record of showing any benefit whatsoever in heart outcomes. Fibrates and niacin lower LDL, among other things, but the bulk of studies don’t show real clinical benefit. A novel drug, evacetrapib, which lowered LDL as effectively as statins, while also radically boosting “good” HDL, failed its trial despite the nice cholesterol numbers; after 2+ years, the placebo group edged it out for fewer heart events. On the flip side, ezetimibe, which lowers LDL cholesterol largely via inhibiting gut absorption, and the newer PCSK9 inhibitors like Praluent and Repatha, which down-regulate LDL receptors in the liver, provide better support for the hypothesis that lowering LDL even on people already taking statins further reduces vascular events.

You get the general picture. For every argument on behalf of the notion that less LDL is better, there is a counter-argument that maybe a very low LDL is not all that useful.

Which brings me to the next — and almost final — point: why not? Why not take a statin, just in case? Statins are notorious for side effects, most of all muscle aches, but the data is really not all that damning. Rates of liver inflammation appears fairly similar to placebo. Ditto hemorrhagic stroke, the risks of which are far outweighed by statin-induced reductions in ischemic stroke. Diabetes is a serious concern, but the actual increased risk in developing diabetes from statin use has ranged all over the map, but remains well below the savings in heart attacks and deaths. Even the muscle pains so many patients complain of after starting a statin might be somewhat of a mirage; this very clever UK study found that statin patients who reported muscle symptoms were no less likely to stop their “medication” when given a placebo trial than a statin re-trial.

Now, I’m not going to say these adverse reactions don’t happen or aren’t real concerns. I have seen most of them among my patients, often in quite compelling fashion (“I literally couldn’t get out of bed after I started that statin; they made me try again and the same thing happened again!”). Fortunately, most of these problems are easily observed and do not cause lasting damage. Liver inflamed? Sugars rising? Muscles hurt? Stop the statin; see if things get better; if they do, start again; if things go badly again, look for an alternative.

I might sound like I have talked myself out of statin agnosticism and into frank statinism. Not so. There is one other problem with prescribing statins for primary prevention: it’s probably better to try first to see if someone can improve their diet, exercise, sleep, stress, and so on.

We will never have scientifically sound numbers to put on this, but lifestyle improvements might amount to 50-60% reductions in heart disease risks. They also can carry other benefits, too, like weight loss, fitness, and unearthed joy, which are hard to find in a 40mg atorvastatin pill.

Sometimes, not uncommonly, my best efforts at carrot and stick fail, and cholesterol levels do not budge. Some of my patients have no interest in taking a medication — but no problem with taking a supplement. Several supplements have intriguing evidence for efficacy, especially red yeast rice, a Chinese flavoring and medicinal preparation of cultured rice. Proper brands will have a tiny amount of the same compound, lovastatin, which was derived from fungi to make the very first statin drug (its creation story is a good read for those curious about the pitfalls of bringing a new drug class to market).

I could fill another Substack with a discussion of red yeast rice, and the medical use of supplements in general, but will just say this: if a patient wants to try red yeast rice for lowering cholesterol, it’s not too hard to tell if it works. In my experience, it often does. Might it share the statins’ ability to improve heart outcomes? A study from China says it does, but I retain my agnosticism there, as well.

I’m not sure if I’ve answered the questions I posed when I started writing this piece. A big part of why I write is to make myself look up the answers to questions I think I already know; often, I change my mind with the effort.

Should we stop pushing statins? I think we probably are a bit too pushy with them. I agree with Dr Byrne; discussing the value of statin therapy with our patients in terms of absolute risk reduction is appropriate, rather than cheerleading for statins by only mentioning their impressive relative risk reduction.

However, I don’t think we should stop prescribing statins for primary prevention. For most people at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the benefits are likely to outweigh the risks, and the harms are not hard to spot.

My own bias, though, is always to make a sincere effort at improving a person’s whole health before reaching for a prescription pad. It’s likely to be better for their heart. Of that, I am not at all agnostic.

Nowhere in this discussion, as interesting as it is, are genetics brought up. In my family there have been no cardiac events of any kind going back to at least my grandfather and including all my uncles, yet we all have or had high cholesterol. My poor father was talked into statins in his 80s and he would tell you that the discussion of side effects was very dismissive--he had terrible muscle cramps until he stopped taking the statins. And, oh, he died recently at 92. I think I'll take my chances and skip the statins my GP keeps trying to sell me.

Nowhere here is the substantial lowering of coenzymeq10 mentioned. Many call it the most important enzyme in your body. It helps the mitochondria in every cell make energy. So your heart needs it more than any muscle. The first statin maker knew this was bad and put it in their formula and then took it out when none of the competitors did. Many say that with it lowered your heart just suffers a slow steady decline that no one attributes to anything. The author just needs to mention NNT too - number needed to treat - with all the horrible side effects the NNT needs to be WAY WAY lower that it is in the studies. Any my last VERY telling question is - uh duh, I guess you could say that Big Pharma likes to use media to push their drugs? At least one out of every three ads now. Where are the screaming headlines and posts everywhere about all the HEART EVENTS BEING AVOIDED? WHERE? They lie in their studies and I am amazed they havent lied in their headlines and stories.