Should We Stop Treating Most Prostate Cancers?

A new UK study suggests "watchful waiting" was no worse than active treatment in lower risk prostate cancers.

Cancer screening is one of the toughest nuts to crack in medicine. Choosing the right screening tool for a given cancer, and then managing positive results so that we actually improve the lives of those we screen, is much harder than it sounds. The poster child for a difficult screening campaign, prostate cancer, is now in the news, with a long-term study from the UK suggesting that treating the majority of men at their time of diagnosis with a low risk prostate cancer is no better than observation:

Since some 85% of prostate cancers are deemed low risk, and early treatment appeared to provide little benefit to this group, another question is fairly raised: “Should we be screening for these cancers at all?” When the Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test was first approved by the FDA in 1994 and feted Desert Storm General, Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., eagerly touted its value, we had a hot new screening tool, one which physicians were encouraged to run once annually on every man over age 50. By the next decade, concerns began to mount that widespread PSA screening had business booming for Urologists, but men were not actually benefitting from the test. Large randomized, controlled trials in the U.S., UK, and Europe showed that PSA testing increased the number of prostate cancer diagnoses, but did not always decrease the number of deaths from prostate cancer, and certainly not overall mortality rates.

By 2012, the U.S. Preventative Screening Task Force (USPSTF) formally came out against using PSA screening at all — ouch:

Against this backdrop, we have this latest long-term randomized controlled study to emerge on managing prostate cancer, the ProtecT trial, a well-constructed twenty year magnum opus in which some 80,000 UK men ages 55 to 69 were offered regular PSA screening, with a prostate biopsy done if the PSA level was found to be above 4 nanograms per milliliter, as well as a bone scan if the PSA was between 10 and 20. Those with evidence of metastatic disease, high-grade pathology findings, or PSA in excess of 20 were excluded from the trial; the 15% or so of men with high-risk prostate cancer at time of diagnosis are in an entirely different cohort than the one ProtecT was designed to study, one for which there is general agreement to proceed with systemic treatment. Those with low and intermediate risk cancers thought to be limited to the prostate gland (i.e., “localized”) were randomly divided into three groups: active monitoring (with escalation of treatment if PSA rose by 50+% in a year or symptomatic concerns were raised), removal of the prostate (prostatectomy), or radiation therapy. What happened over the next two decades?

The headline result as it ran in the New England Journal of Medicine was that prostate cancer deaths were similar in all three groups, implying a lack of benefit from early treatment:

Viewed alongside the lack of overall improved survival and that impressive 98% follow-up rate, it’s tempting to conclude that rushing into treatment after a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer is a loser. However, the value of the ProtecT study has faced a good bit of questioning from the world of urologic oncology. The same NEJM issue held an editorial from one Dr. Oliver Sartor, who raises the point that the treatment algorithm utilized in the trial is outdated. In his words, “That simplistic approach has dramatically changed in the wake of evidence that has been gathered since 1999.”

There, really, is the rub when trying to issue evidence-based recommendations on cancer screening. To perform a proper trial of this sort, it takes time (in this case, 20 years), the time to accrue enough cancers and deaths to make meaningful statistical comparisons. The problem — aside from how hard it can be to generate enthusiasm and funding for a study with an end date which might exceed the lifespan of some its researchers — is that technology advances, studies are published, and practices shift while the study lumbers on.

In the world of prostate cancer screening and treatment, a good bit indeed has changed since 1999. Dr. Oliver reviews the developments in his editorial. Now, as is typical, most advancements involve extra expense, like coupling a pelvic MRI (cost on my expensive island: roughly $2000) with an elevated screening PSA to help stratify risk and lead to a targeted biopsy if necessary; or, more recently, utilizing prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) radiotracers with a PET scan (not available in my state, and probably more than double the cost of MRI) to even more accurately look for spread of tumor cells outside of the prostate. We also now have a range of genetic tests available both to screen for higher risks of inherited vulnerability to prostate cancer, and with which to test biopsy samples.

Of course, the medical-industrial complex is real, and Dr. Oliver’s Conflict of Interest disclosure literally is four pages long, and involves most pharmaceutical companies I have heard of and several new to me. Do we really know that the increasingly common practice of performing an MRI for those with moderately elevated PSA levels improves outcomes? Based on another recent NEJM study, it would seem so; the results were enticing, after all:

To explain a bit more, as the use of MRIs has greatly changed the landscape of prostate cancer screening and treatment, what they did was randomize men with elevated PSAs to either get an MRI-targeted biopsy in the area of greatest concern versus having a systematic biopsy of the prostate (i.e., the “pin cushion” approach) as well as any areas of high suspicion based on the MRI. Biopsies are graded with the unintuitive Gleason score: two numbers, the first of which is the degree to which prostate cells have become altered on the spectrum from normal to malignant in the most commonly seen cell pattern, and the second of which is that same score for the next most common pattern. Furthermore, what was once a 0-5 score has been changed to a 3-5 range (presumably to confuse non-urologists as much as possible), so that a 6 out of 10 (always a “3+3”) might sound pretty serious, but is actually considered by some a mere “pseudocancer.” A Gleason 7, if a “3+4” with the predominant pattern being reassuring, is thought to be low risk prostate cancer; but if “4+3,” with the more concerning pattern more prevalent, more likely to spread and cause serious disease.

Yes, the above study graphic implies that using MRIs to guide biopsy choices could cut in half biopsies which find “pseudocancers,” thereby reducing these uncomfortable and expensive procedures which occasionally result in serious adverse effects. That MRI-guidance only missed a low rate of Gleason 7 cancers, all of which were of the less aggressive “3+4” variety, suggesting that little would be lost via all those saved biopsies. However, Oncologist Vinay Prasad raises the fair point that decades of understanding the long-term behavior of prostate cancers with a given Gleason score found on systematic biopsy might not translate to Gleason scores only gleaned from lesions that looked suspicious on an MRI. The only way to really find out, of course… a long-term study, by the end of which Urologists probably will be saying that the results are garbage, “since everyone uses PSMA PET now, anyway.”

Regardless of whether the addition of MRI technology to the triage of elevated PSAs has made the algorithm followed in the ProtecT trial obsolete, other valid concerns have been raised. As Dr. Oliver pointed out, the average “high” PSA was barely elevated, in the mid-4s (a typical normal range runs up to 4), and the vast majority of prostate cancers in the trial were of a very low risk variety. In other words, a study with higher risk individuals might have found benefit from more aggressive treatment. What’s more, there was a benefit to initiating treatment: halving the rate of metastatic disease — roughly 5% in the treatment groups vs 10% in the active monitoring cohort. Avoiding the anxiety of metastatic disease, and the side effects of systemic cancer therapies, is a significant benefit! The other important point is that, for most of those undergoing watchful waiting, they ended up needing treatment eventually.

A steady trickle over time, but by 15 years out, over 60% of the active monitoring group had received surgery and/or radiation therapy for their prostate cancer; only 24% were alive, free of radical treatment, and without evidence of advancing cancer. Since that’s the cohort every single patient wants to be in when choosing to delay intervention, it’s fair to wonder if the wait is worth it.

All in all, I’m inclined to side with the Urologists who are shrugging off the significance of this seemingly impressive study. Yes, it reassures us that delaying treatment for a patient with a high PSA but low or intermediate risk of aggressive cancer is probably a fine approach; but that’s the approach we’ve been taking for years now, anyway. The harder questions have always been what to do with more borderline cases, like intermediate Gleason scores but other risk factors like African descent (Black Americans are about twice as likely to die of prostate cancer) or a strong family history of breast cancer (yes, the BRCA genes which greatly increase the risk of breast cancer in women have been shown to very roughly double the risk of invasive prostate cancer in men); or men with more severe disease but in poor health with a high risk of dying from their comorbidities before their prostate cancer.

The hardest question of all around prostate cancer, however, remains: should we still be screening men with the PSA test at all?

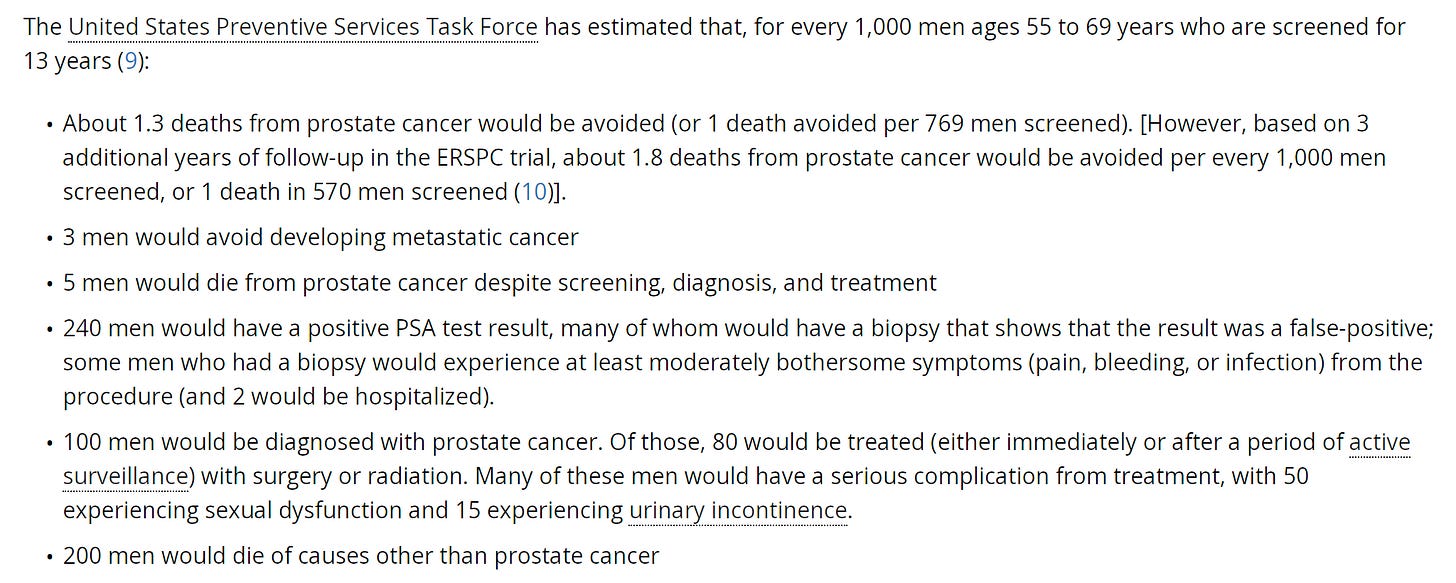

Currently, the recommendation is that the decision should be a “discussion between doctor and patient.” It’s a nuanced discussion. This NIH report frames the USPTF numbers well:

Consider those numbers: charitably, a screening program which promises two “saves” per 1000 screened over 15 years (another three if we count catching cancers before metastasis), but no net mortality improvement. Five die of prostate cancer, anyway. Almost 25% end up with the stress and anxiety of an elevated PSA, slotting them for an uncomfortable biopsy (done as an outpatient, with a needle taking multiple samples either through the rectum or perineum) which will put two of the 1000 in the hospital, usually from infection. Ten percent end up with the real burden of a cancer diagnosis, despite the majority of that 10% being destined to die of other causes had they never been told they had prostate cancer.

It’s a bit of a tough sell.

For the average 55-year-old man, I might frame it this way: there’s about a 1/200 chance you’ll really benefit from PSA screening with a life-altering result, about a 15% chance you’ll mildly regret it (with a false-positive PSA that leads to a minimum of a pelvic MRI, if not a negative biopsy), and about a 2% chance you’ll really regret it (an unnecessary cancer diagnosis that never ends up needing treatment), plus a number north of there of men whom we think need to be treated, often end up with long-term side effects from treatment, but would have died of something else anyway had we not treated them. Is the upside over possibly avoiding systemic treatment for advanced disease or even death from prostate cancer enough to justify a fourfold greater risk of anxiety over being told you have prostate cancer when really you “didn’t need to know?” Are the expense and logistics of a massive cancer screening and treatment program worth it, when we don’t expect to see a net saving of lives?

These are hard questions to answer. With apologies to urologists, radiologists specializing in pelvic MRI, and radiation oncologists, I don’t think every 55-year-old man should be encouraged to get a PSA given the current evidence. The Holy Grail of cancer screening would only flash positive for aggressive, life-altering cancers, and always run negative for indolent tumors that don’t pose a risk. The PSA is far from this ideal. The new darling of urologists is the IsoPSA test (cash cost: about $450), which offers the hope of reclassifying around half of elevated PSAs as likely benign and not in need of biopsy. In late 2022, Medicare opted to cover this test for men with a PSA in the 4-25 range; my main concern is that their coverage determination is quite clear that none of the trials in support of IsoPSA have even included a control group, not to mention long-term follow-up of outcomes.

Still, I try not to be one of those doctors who thinks what he was taught while training in 2005 will always be the one true path. Those cost:benefit numbers from the NIH are pretty close to a wash for a lot of average-risk men. Screening might sound like a clear win for men in good health who don’t mind some extra poking and prodding, and cannot stand the idea of not screening for a cancer which does, after all, lead to the death of 1 in 40 men. For men whose risk of an aggressive prostate cancer is probably about twice average — Black Americans, men with a first degree relative with prostate cancer or multiple more distant relatives, men with strong family histories of breast cancer, especially if known positive for BRCA mutations — I think the numbers clearly favor PSA testing, perhaps starting as early as 40, especially if there is a family history of prostate cancer diagnosed before age 60. I’m also not stuck at stopping at 70 or even 75 years of age, if a patient is in particularly robust health or is of unusual prostate cancer risk.

I have always warned my patients enamored of PSA testing, “This is a great test… as long as it comes back negative.” For the unfortunate but substantial minority who will end up with an elevated PSA, I reluctantly join the modern age and recommend an IsoPSA and/or pelvic MRI before sending them on to a urologist for biopsy and further decision making. I would prefer the data to be better for both, but any technology that promises to cut the need for biopsies in half has my support, given how unlikely it is that a little extra waiting will cause harm to my patient.

And that, really, was the greatest value of this recent ProtecT trial: “hurry up and wait” continues to be a fine mindset for patient and physician both when confronting a high PSA, and even a biopsy-proven low or intermediate risk prostate cancer. These are not fast-moving malignancies. I was taught that all men lucky enough to live to be 100 will have prostate cancer on their autopsy. We can not, and should not, try to catch and treat every tumor lurking in mens’ prostate glands. Somehow, an organization with the mission to “end prostate cancer” and “imagine a future with zero prostate cancer deaths” has managed to survive for decades with this motto:

I’m sure they are a well-meaning bunch. So, too, are those who cannot bear to leave a potential prostate cancer unscreened or untreated. However, when facing a nearly ubiquitous cancer, we have to strive to balance the goals of prevention with the avoidance of over-diagnosis and over-treatment. In the case of prostate cancer, that means one-size-fits-all recommendations can’t suffice.

Truly, it’s cause for honest conversation between doctor and patient with individual choice at the forefront. Sometimes it’s better not to know you have cancer, and sometimes the cancer you know you have is best left untreated. Medicine, like life, is hard.

The recent questions over the value of colonoscopy for colon cancer screening which I wrote about last year are a fair example of this dilemma.

Usual thorough evaluation, difficult topic

The gamble is; will l die of something else before I die of prostate cancer. If I were overweight, a heavy drinker, junk food junkie, that didn’t work out religiously, I would bet I don’t die of prostate cancer. Whoopi.