Was Tom Cruise Right About Antidepressants?

Yet another article challenges the "chemical imbalance theory" of depression, but it doesn't mean we should abandon SSRIs.

17 years ago, back when Tom Cruise was young and Matt Lauer still had a job, the two had an uncomfortable interview on the Today show. Really uncomfortable. After chummily discussing Cruise’s engagement to Katie Holmes, the conversation chilled when it pivoted to the topic of Brooke Shields and her use of antidepressants. This rankled Cruise and his Scientologist beliefs, and at one point he snarled, “There is no such thing as a chemical imbalance in the body.”

A paper published last week in Nature drew a remarkable amount of attention, with its assertion that there was very little evidence to support the so-called “serotonin theory” of depression, that a deficiency in brain serotonin transmission is a primary driver of depressive disorders. Their concluding paragraph:

In other words… Tom Cruise was right. Well, at least about that. The review authors did not weigh in on Scientology or the wisdom of marrying Katie Holmes.

Of course, Twitter noticed:

While I am very happy for Tom Cruise and his medical vindication, I am more interested in how the hype around this study affects our view and use of antidepressants. Is it time to fire our psychiatrist and toss out our selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) prescriptions? I think that’s a poor interpretation of this work. However, a critical appraisal of the value of antidepressant medications is worth our societal while, especially since approximately 15-20% of American adults have taken antidepressants in the past month, mostly SSRIs.

A first important point to make, well known to those who have followed psychiatry in the past decade, is that the “chemical imbalance” theory of depression largely has already been abandoned. After all, the Nature paper was an “umbrella review” — namely, a review of other reviews and meta-analyses — so everything they covered was old news. They picked and chose others’ work along 6 lines of research into serotonin’s role in depression, and found little evidence of effect anywhere. I do note that these authors have published on this subject before, with similar findings, and one advantage of authoring an umbrella review is that you get to chose which studies to include, and which to exclude for being “low quality” or too old or poorly designed.

In any case, I don’t see psychiatrists rushing to defend Matt Lauer’s 2005 position. One can make the point, as the review authors do, that some prominent voices in psychiatry continue to imply that a chemical imbalance is behind depression, and that this has gained too strong a grip on the imagination of the American public and many doctors. (Here is such an argument.) Fair enough; the medical establishment, and the pharmaceutical industry, should let go of this concept.

However, abandoning the central role of serotonin in depression is not akin to abandoning the medications, Serotonin Selective Reuptake Inhibitors (“SSRIs”), which affect serotonin levels around the brain’s synapses. That’s the real question here: do SSRIs actually work, even if they don’t work the way we once thought they did?

To be fair to SSRIs, it’s worth pointing out that we don’t know how a lot of medications work; we just use them. Even some of the good ones like Tylenol and metformin still have their secrets as to just why they work. After indulging myself in bunches of psychiatry podcasts this week, I’d say there is something approaching consensus among media-facing psychiatrists that while the actual effect of SSRIs on neurotransmitters remains somewhat of a mystery, the global effect on patients seems to be one of reducing emotional intensity. If your being is dripping with joy, this might not be a good thing; but if depressive feelings overwhelm, or anxiety, PTSD or OCD rule the day, the appeal is obvious.

One more thing to say, before digging into the SSRIs themselves, is that the need for effective treatments for depression is high on any doctor’s list. Depression is common; it can be debilitating; and even when mild, it can strip the richest life of meaning. Some seem to come by their depression via genetics, others by life circumstance, and still others by physiology; but whatever the trigger, a major depressive episode chugs along in a complex and poorly understood mix of emotion, behavior, and neurobiology that alters the way the brain functions. Anyone who has watched a friend or family member struggle with depression knows: this is not mere sadness that can be pushed aside or ignored. Clinical depression is a medical condition. Strong is the temptation to wield a silver bullet to alleviate all this suffering, and herein we find the massive market for SSRIs.

I should say this now, as full disclosure: I’ve never been a big fan of these medications. In fact, one of the only times I’ve ever been yelled at by a fellow physician was a psychiatrist deeply angered because I had defamed all of psychiatry when I suggested to a mutual patient that SSRIs might not be much better than a placebo. (The other time came courtesy of an irate Cardiologist when, fresh out of residency, I sent a patient out of the ER via air ambulance based on my misreading his EKG to be a potentially fatal arrhythmia — that’s a tongue-lashing I earned.)

That said, I have treated enough patients with depression to know that some of them have compelling stories that SSRIs, and only SSRIs, help them out of their depressive episodes. If we look at the evidence, we see that their experiences are probably more than just anecdotes.

The evidence on SSRIs in treating depression is complex, to be clear. There are plenty of positive studies out there dating back to the 1980s which might convince you that SSRIs are better than sliced bread; but there is also the reality of publication bias. The vast majority of drug trials are sponsored by the pharmaceutical firm that makes the drug. When it comes to SSRIs, the majority of drug trials never get published, because the drug company in control of the trial doesn’t want them to be published, due to a negative result.

This practice led to the meta-analysis which delivered me that brow-beating at the hands of our not-so-friendly local psychiatrist. In 2002, Irving Kirsch, a psychologist on the Harvard faculty, sought the data from all registered trials on antidepressants from the FDA through the Freedom of Information Act. He had co-published with Guy Sapirstein a meta-analysis on antidepressants in 1998 which had shown little benefit in their use over placebo; now, he had access to the half of antidepressant research which had never been published, including the 57% of studies which had not shown any benefit at all over placebo. The result? The average antidepressant (with the same results for SSRIs as for older medications) showed a solid reduction of about 10 points on the Hamilton Depression Scale, a decades-old clinical tool for measuring depression that scores a patient’s depressive symptoms from 0 to 52. The catch: the average placebo dropped it over 8 points. The difference between medication and placebo was too small to meet the pre-determined threshold for clinical significance of 3 points, i.e., a difference that would amount to a worthwhile improvement for a depressed patient.

Understandably, his work (repeated in 2008) turned psychiatry on its head and created a huge wake of controversy. Now, I would be remiss not to note that Kirsch already had a field of interest before beginning his work on antidepressants: the placebo effect. This concerns me slightly. Why?

Roughly speaking, there are three types of researchers in the world of science. Some are out to prove what they already believe, due to a desire to buttress their academic or intellectual standing, or an innate drive to confirm their convictions. Others are out to prove what they already believe, as their opinions are owned by commercial interests. And others are genuinely curious. Obviously, I prefer scientific literature from the final category. Unfortunately, such scientists produce a tiny fragment of the world’s research. We’re generally left sorting through less nobly-inspired efforts.

So, much like the Nature paper that put Twitter in a time warp back to the Today Show circa 2005, it’s possible that this research could be biased. I don’t say this to impugn or discredit Dr Irving, whose efforts I greatly admire (and have been roughly replicated by others, as well as challenged). I say it to remind myself and my readers that even extremely convincing scientists sometimes have their work compromised by their own biases.

For a counter-point, I turned to Dr. Scott Alexander Siskind, a psychiatrist whose “rationalist” blogs on a massive array of subjects have inspired a devoted following. I appreciate how his mind works when he discusses medicine, and rarely disagree. Rather to my surprise, Siskind actively defends SSRIs, despite acknowledging their evidential shortfalls.

His first point is fair: questioning whether the technical rating scale used in Kirsch’s meta-analyses is the best way to measure depression. He points to one recent study on the SSRI sertraline as evidence that simply asking patients if they had improved gives about twice the effect size of performing a formal scale. Not terribly compelling.

Siskind’s second point is also fair, namely that any SSRI trial will have responders and non-responders, including some whose depression scores might worsen during treatment. Hence, some proportion of candidates for an antidepressant will have better-than-average responses; perhaps a sizeable number will have a clinically meaningful improvement. However, he provides a single link only to a research protocol, not a study; and when I search for literature on this subject, I found only a study redacted for technical flaws. Again, this is a possible argument for benefits of SSRIs hidden in negative trial data, but not a very persuasive one.

His final case for continuing to prescribe SSRIs despite the mediocre data is, essentially, “what else is there to do?” It’s not ethical to prescribe a placebo to a patient, so we are stuck prescribing a class of medications that work best as a placebo, but carry all kinds of side effects, from sexual dysfunction (very common), to drug-drug interactions (sometimes an issue), to bleeding disorders (thankfully relatively rare), to the worrisome difficulty some patients have tapering off their meds once started. His words:

Here, I strongly disagree. We can give out placebo, with ethical integrity intact! First, though, it’s worth a few words about the placebo effect, which is badly misunderstood by the lay public, and most physicians, too.

The placebo effect, describing the occurrence of positive effects based on the expectation of receiving treatment (and its shadow sister, “nocebo,” on the negative side), is not limited to expecting to feel better and therefore more highly rating the exact same experience. To be certain, some of the placebo response seen in a study stems from this sort of over-rating; if I take an ibuprofen I might be inclined to describe my aches and pains as milder than if I had not, simply due to an altered perspective. Some hunk of placebo group improvement also is due to the passage of time, regression to the mean, and the ability of the mind and body to heal itself, whether it’s depression or ulcerative colitis being studied. Both of these contribute to placebo response, but are not a true placebo effect. However, some people genuinely, physiologically, heal at a higher clip if they think they are being treated than if they think they are not. People actually get better when they expect to get better!

Dr. Kirsch, our placebo aficionado, unsurprisingly addressed this very subject; he found that trial subjects only going through the motions in antidepressant studies (i.e., enrolling and being followed within the trial, but not given either active medication nor placebo) had about half the improvement of those given the placebo. He also cites a small study which found that those given placebo, while experiencing nearly the same response as those given actual antidepressants, had roughly five times the response as those given only supportive care.

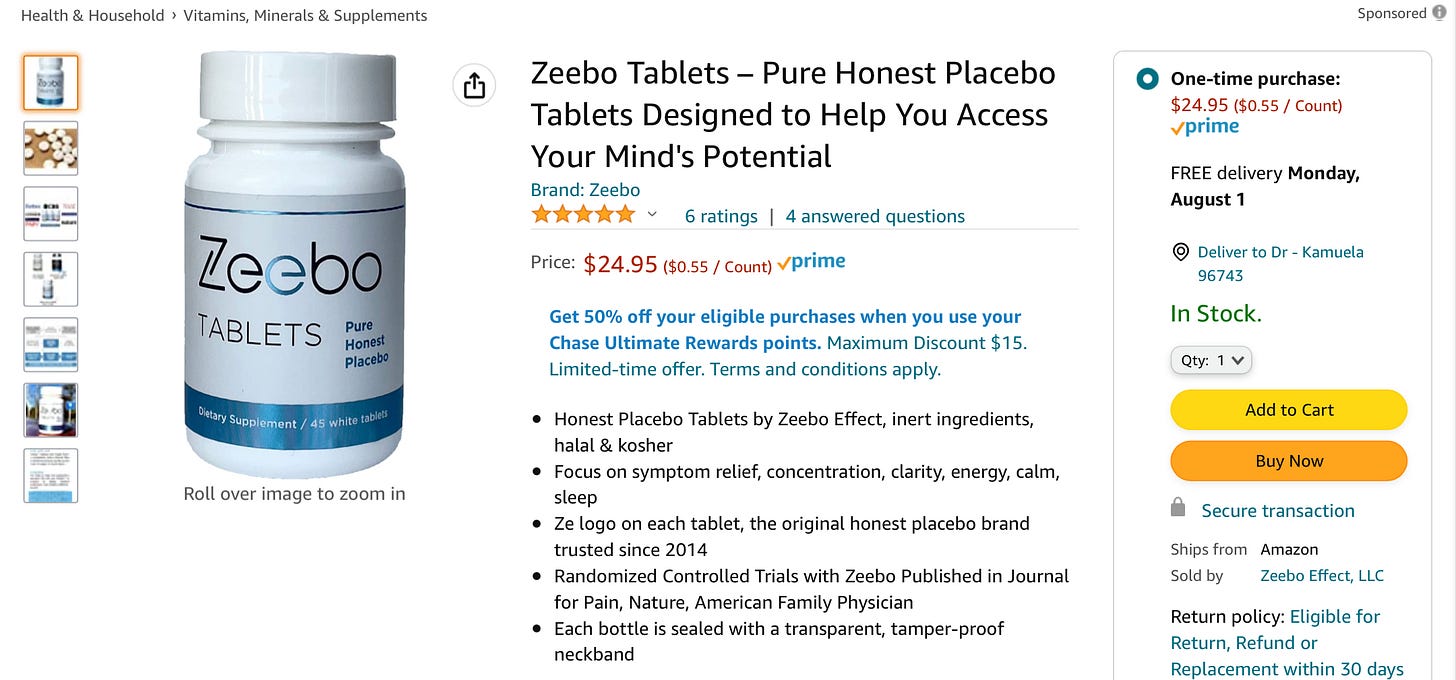

Just to make this even weirder, there is more and more evidence that so-called “open label placebos” work quite nicely, too, including a recent meta-analysis with an effect size across multiple fields of study that, ahem, rather exceeded that of SSRIs. Yes, presumably through the magic of conditioned responses, even when patients know they are being given a placebo, they still get better, beyond mere regression to the mean or symptom misrepresentation. And that is why you can go on Amazon and buy this:

I’ll be honest — $25 just feels high to me here — but it’s hard to argue with the risk:benefit calculus.

So, that’s where we are with SSRIs: high rates of side effects, with probably only a slim benefit over placebo. To further muddy the waters, Kirsch argues that much of that slim benefit might be due to the “active placebo” effect of taking a medication with obvious side effects which might serve to further enhance the placebo effect! Some studies, however, dispute this claim by finding that study participants who complain of side effects don’t get better outcomes.

For now, at least, I continue to believe, based on the balance of current evidence, that some subset of patients experience a modest, clinically meaningful response to SSRIs.

However, I think any rational physician would review the evidence and conclude that placebo is a better option than SSRI for typical patients seeking care for depression (I want to be clear here that I am not advocating giving a placebo medication to actively suicidal or otherwise dangerously ill patients). If you took every antidepressant trial, labeled placebo, Drug X, and the active medication, Drug Y, listed the outcomes and adverse effects for both, and told physicians that they could prescribe either one, I am rather confident Drug X would be deemed the better choice out of virtually every SSRI trial. But how can we prescribe a placebo?

I do think we have an excellent option in this regard: supplements. We have lukewarm data to recommend multiple options in this realm, from serotonin precursors like 5-HTP and L-tryptophan to the vaguely SNRI-like SAMe and SSRI-like St John’s Wort. Yes, the studies are small, often funded by supplement-makers, and often use none other than SSRIs as their gold standard comparison; but as long as patients avoid contaminated batches (witness the tainted L-tryptophan nightmare of 1989, with 36 fatalities) and the occasional drug-drug interaction (several theoretical concerns with St Johns Wort and medications from blood thinners to HIV meds), I find the side effect rate to be extremely low with these options.

That’s my usual pitch when a patient with mild or moderate depression comes into my office, wondering about a Prozac prescription. I run through the efficacy and side effect concerns of SSRIs, and offer that a supplement might be better tolerated and work virtually as well. I always allow that any improvement might be pure placebo effect. Of course, if they’re willing to engage with therapy, take up meditation, exercise more, eat and sleep better, and do more of the things that once brought them joy: these are probably the best tools, without any side effects. Dr Siskind posted an informal review of the different approaches to managing depression which I think is an excellent resource.

Some of my patients, due to past experiences, or those of family members or friends, will want to start with an SSRI. Most of them will get better. I’ll never know whether it was the medication — or something else.

I will encourage a trial off the SSRI once they’re better, to limit their exposure to possible adverse effects. Whether longer stints on SSRIs reduces the risk of future depressive episodes by “protecting” the brain from the ravages of depression, or instead actually lead to a greater risk of relapse, I don’t know; evidence and opinions are all over the place.

I do know this, though: when Tom Cruise gets so worked up talking about psychiatric medications that he starts calling me by my first name, once or twice in every sentence, and not at all in a friendly manner, I’m cutting that interview short. Right then and there. Even if he is right.

I appreciate I might be a lucky exception, or it may be the placebo effect, or just coincidences, but because you're curious I'll tell you my story. Nearly ten years of depression that started when I was in my early 20s, after a very traumatic year during which my father nearly died, received a transplant, nearly died again, and then nearly died again, before he finally got better. Then harsh immigration laws forced me out of the life I had built for myself in the last five years and back into my home country, living with my grandma -- and found out she had alzheimer's and was not capable of handling herself anymore. Took care of her for a couple years while working on a project I truly believed in with a partner whom I trusted but ended up running away with all the credit and the money (I should have signed a contract).

Then I moved to yet another country, life was getting better but by then I was strongly under the grip of depression and it was difficult to find any joy. For years I pretended to smile, I was just barely hanging in there. For years I was lonely despite having many friends. Then came Covid, and I lost my job, and at the same time a child relative of mine who, I deeply care about developed a life-threatening rare disease. A friend of mine flew from across the world to help me through this and saved me. Then I started working on another project, with another partner I trusted, with another partner I did not sign a contract with, and I ended up losing $60k+ to that (all of the money I had saved up). While all of this was going on, I also broke up with a person whom I thought was the woman of my life. (I don't blame her, I was a sad mess).

One close friend who had been through depression told me that what I was experiencing was not normal (I had come to believe it was and in fact was seriously entertaining the delusion that every single person in the world was depressed and everybody was just pretending to be happy while deeply suffering inside), that I go get treated. I'd never wanted to get treated cause I never wanted to consider myself sick.

I was in quite a bad state at the time and I couldn't even get on the phone to call a psychiatrist. I had to have a friend do that for me, and I had to have another friend drive me to the appointment. After the appointment, the psychiatrist initially insisted on giving my prescription to my friend because he was afraid I'd take my own life -- despite not having mentioned any suicidal ideation, even though by that point the only reason I did not let myself die was because of other people in my life whom I could not give up on. I was given Lexapro, diagnosed with severe depressive disorder and general anxiety disorder.

Maybe it's the placebo effect. Maybe it's a complete coincidence. But within a month, I started feeling exponentially better. I still remember the first morning that sung again. I was in the shower and I heard somebody sing something in the street, and I thought - oh! life is sometimes so beautiful and graceful! A few months later, I had the energy and self-esteem and self-respect to tell the man who was exploiting me and my money to fuck off. Unfortunately, I had a close relative die and relapsed for a few months, isolating myself far away from the city where I live in. But even those times I "relapsed" I was still significantly better than I had been a year prior. Unlike before, I knew some measure of happiness was actually possible and I was confident it would come back. It took many months, it took exercise, and beyond that it took great support from my friends - but I am now NO LONGER DEPRESSED. I still have my difficulties and flaws, I still have a hard time waking up in the morning, but once I wake up, I go and get shit done, and at the end of the day, I go exercise, and after that I'm pretty happy with myself. There are many more things in my life I need to take care of, but they're getting taken care of, little by little. I have built a much more resilient life. I continue to meet difficulties and challenges but I confront them head on rather than run away from them or duck my head in the sand.

Lexapro and exercise were my only lifestyle changes in that period. Consequently, I credit them with getting better. And I started getting much, much better within a few months of taking them, with noticeable improvements from week 3 onward. I was actually surprised because I didn't think it was gonna work and I had previously been hostile to taking antidepressants. And as an avid reader of Scott Alexander's blog I know that despite his advocacy the data isn't strong.

Maybe all of that is a big coincidence, but my personal opinion is that it is not. I seriously went into this treatment believing it was not going to work. I am an intellectual person, I follow psychiatry, and I was not at all a proponent or follower of the serotonin theory of depression. I tried this because I felt I was out of options and today I'm still not a proponent/follower of the serotonin theory of depression, but I do believe in my particular case Lexapro had a decisive and very significant effect. I feel it got me my life back.

SSRIs did the heavy lifting (no pun intended), but lifting weights has definitely helped also. Now I'm at a point where I believe I'm ready to go off-meds; I won't do so brutally and without adequate supervision, but I think I have a strong enough life now that I can do without them and be fine -- knowing I can always go back to them if needed.

A local clinician prescribed these to my wife after misdiagnosing her gluten intolerance as being all in her head.

She only took them a year (before they finally had her scoped and discovered she has celiac) and she had to be checked into a clinic to detox off of them for two weeks.

I have always believed that the sitcom Frasier was the most accurate representation of modern psychiatrists to date, and, that the whole industry took off when Ritalin became the 'wonder drug' to control unruly kids. Those kids are still taking meds.