Pfizer’s Maternal RSV Vaccine Falls Short

A poorly elucidated risk:benefit ratio probably won’t stop it from being approved, however.

Back in November, I wrote about Pfizer’s press release for their ground-breaking new maternal RSV vaccine, RSVpreF. The news was exciting — respiratory syncytial virus lands some 1-2% of U.S. infants in the hospital in a typical year, and an effective vaccine has been long overdue. I was cautiously optimistic, but expressed concerns over two issues: will their safety data hold up given that competitor GSK’s maternal RSV vaccine trial was stopped for adverse outcomes, and how will efficacy look once all the data is published? Well, in yet another example of “why you can’t trust a press release,” all that glittered was not gold. I no longer have a positive opinion on the RSVpreF vaccine.

Now, this is not to say the vaccine failed utterly; the study results as reported last week in the New England Journal of Medicine were not altogether out of line with that enthusiastic press release from the fall. At 90 days after birth, infants of mothers who received the shot were 82% less likely to have experienced a severe case of RSV; and at 180 days, there was still a 69% lower rate. We were reassured that adverse incidents were similar between vaccine and placebo groups beyond the usual post-injection complaints. All in all, the results were met with enthusiasm:

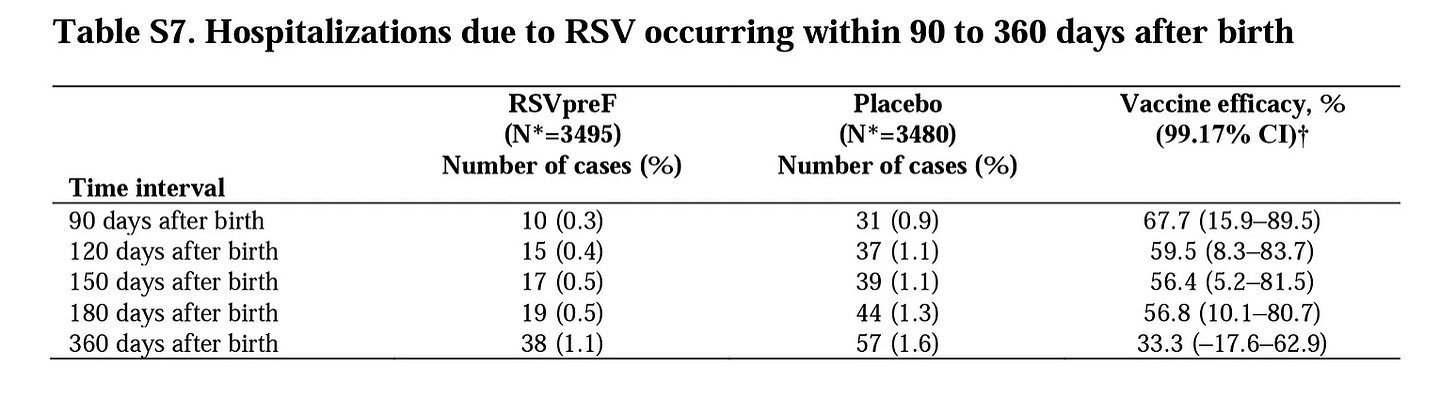

I am not going to pick the entire study apart; that’s done well by a medical student, Dave Allely, here. Instead, I will focus on two numbers. First, as regards efficacy, the primary outcomes of interest were those 82% and 69% reduced rates of severe RSV at 90 and 180 days (as well as overall all-comer rates of medically-attended RSV, which was a more modest 57% reduction which did not meet the pre-determined criterion for a successful outcome). These shorter time frames make sense from Pfizer’s perspective, as we would expect the effectiveness of a maternally-administered vaccine to wane with each month after birth. However, from a physician’s perspective, the outcome in which I was most interested was the secondary outcome of RSV hospitalization, with data out to 1 year after birth; this data went conspicuously unmentioned in the November press release, despite Pfizer having shifted the outcome measure mid-trial from 180 to 360 days. Sure enough, it’s a bit less inspiring:

Now, I would rather prevent severe RSV in the first 6 months than later in life, if forced to choose, as the mortality rate is moderately higher in younger infants than older infants and toddlers. However, a hospitalization is still a serious event at 9 months or a year, too, and as a parent, I don’t suddenly lose interest in how effective a vaccine is after my baby is 6 months old. What we see in the above table is that the RSVpreF rapidly lost efficacy after 6 months, with hospitalizations suddenly accruing at a faster rate among the vaccinated cohort than placebo (19 cases vs 13 over those 6 months). Whether statistical noise or a signal that altering the usual transmission dynamics in infants could have unforeseen drawbacks, it undermined most of the benefit of those first 6 months, with only a 33% reduction in hospitalization remaining that was not statistically significant.

So… the benefit of taking this vaccine for an expectant mother does not clearly exist over the full length of time in the trial. We do have a “trend” — i.e., improvement lacking statistical significance — implying that 1 in every 200 infants would be spared an RSV-associated hospitalization in the first year of life through this vaccine.

What about the cost, though? Here is where the authors seemed particularly unwilling to address the elephant in the room. As I wrote in my November post, no one touting Pfizer’s promising results was mentioning how exactly they avoided GSK’s safety concerns while testing a similar product in their trial. The details of what went wrong with the GSK trial was still not publicly available in the fall; however, the safety signal was revealed via a scientific abstract in February 2023:

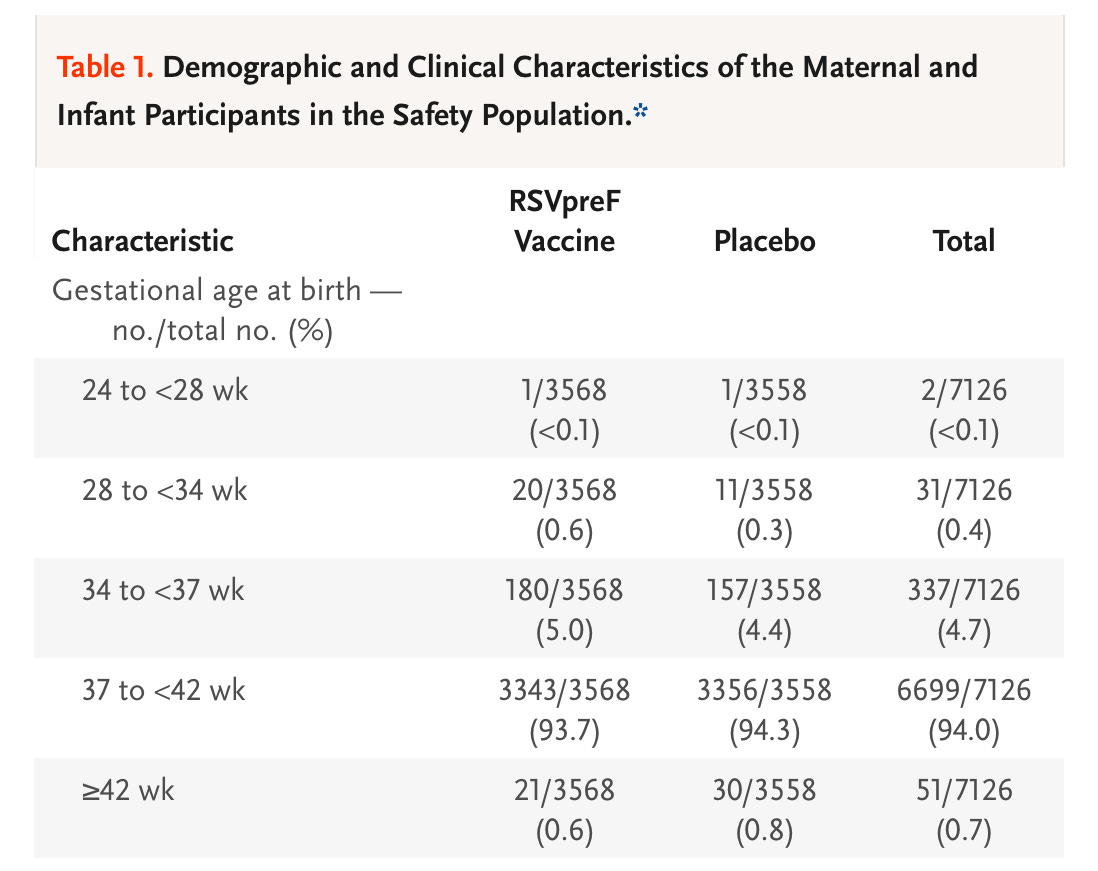

Well, how did Pfizer’s product stack up in this one regard? Not well!

A 5.6% rate of pre-term birth vs 4.7% among the placebo group if we use 37 weeks as our cut-off; and at the more significant cut-off of <34 weeks, at which there can be substantial short- and long-term repercussions of pre-term birth, we still see an absolute difference of 0.25%. To be clear, even so-called “late pre-term birth” is not a trivial matter; births in the 34-37 week range are at greater risk of complications than term babies.

So, if the signal found in the trial were to hold up with larger scale data, we would see an increase of almost 1 in a 100 additional infants born pre-term to mothers given the RSVPreF. 1 in 400 would be born earlier than 34 weeks. Will these findings hold up in the real world with more numbers? The larger GSK trial certainly suggests there is a legitimate chance they would.

Of course, our numbers are limited because Pfizer’s MATISSE trial for RSVPreF was stopped early — because it was so effective! I am confounded by the regulators who saw fit to stop a trial early with a major, easily-anticipated safety signal not yet fully delineated.

It also leaves me unable to recommend this vaccine to my patients. The risk of preterm birth is simply too high to advocate for its benefits; if we are guided by the limited (and not statistically significant) information we have, the best guess we can make is that the improvement in hospitalizations over one year (1 save per 200 vaccines) is eroded by the potential for additional pre-term deliveries (1 extra per 110 vaccines, with 1/400 early pre-term before 34 weeks). Especially when it comes to pregnant women and infants, “first do no harm,” right?

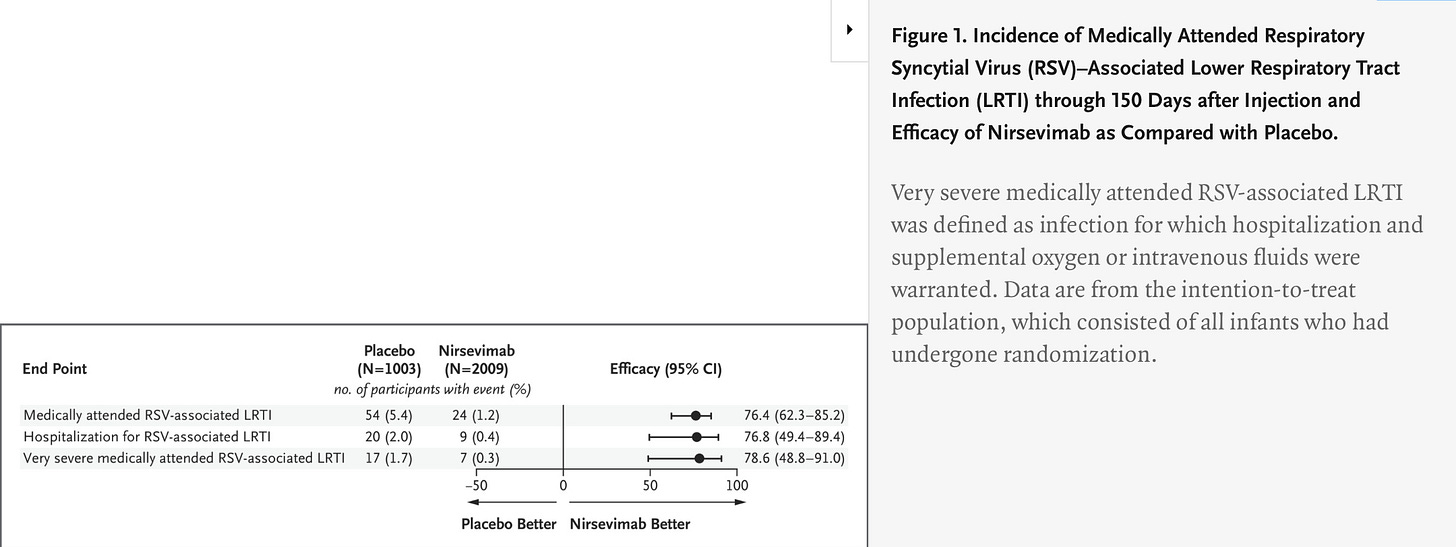

The other factor in why this trial data amounts to a failed vaccine for me is that we are about to have a perfectly good alternative. I am sure it was not a coincidence that in the same NEJM issue, we had correspondence reviewing the updated trial data for AstraZeneca’s monoclonal antibody, nirsevimab, already approved in the UK and EU for late-pre-term and term infants to prevent RSV. It essentially meets or exceeds the efficacy data for the RSVPreF vaccine, with 78% reduction of hospitalizations at 5 months, as well as reducing overall cases of medically-attended RSV:

Unfortunately, they did not collect efficacy data beyond 150 days, but their efficacy figure exceeds that of the Pfizer vaccine at 160 days.

As to safety, rates of overall and severe adverse events were quite similar in placebo and nirsevimab groups. Adults with the new Covid-19 monoclonal antibodies had tolerable but concerning severe allergic reaction rates, but none were seen among infants given nirsevimab. The only safety signal of concern was the report of 4 deaths in the ~2000 members of the nirsevimab cohort, with none in the ~1000-strong placebo group. None were within 4 months of their intramuscular injection of nirsevimab, and I find the list below reassuring that there is not likely a genuine increased risk of all-cause death after receiving nirsevimab:

Obviously, this safety concern can be tracked with post-marketing data, as deaths in the U.S. among infants are rare. The same can probably not be said for RSVPreF, for which I expect approval with a plan to track post-marketing data on pre-term births. The problem, of course, is that pre-term births are common, often without a known cause, and we will lack a control group and be left with a “historical cohort” for comparison. If the FDA approves RSVPreF without requiring further randomized controlled trial data to elucidate the risk of pre-term birth, we will probably never be able to accurately assess this risk. I am not optimistic that more trial data will be demanded, however.

So, in short: I doubt I will ever be able to recommend Pfizer’s RSVPreF to pregnant women concerned with the risk of RSV hospitalizing their infant. At this point, AstraZeneca’s nirsevimab has a clear advantage, and I would offer to infants with high risk due to medical conditions, limited access to care, or high exposure risks. RSV is not a trivial concern to infants. It’s unfortunate that Pfizer could not convince with its maternal vaccine study.

I highly recommend watching leading "anti-vaxxer" Del Bigtree debate Neil DeGrasse Tyson. Decide for yourself who seems more credible. https://thehighwire.com

While I appreaciate that preterm is very serious. I think we need to take a crash course in statistics.

The difference is not statistically significant. What does that mean? Well if you don't know and haven't run the statistical analysis - TTEST, Fisher's exact test etc. You really shouldn't be making conclusions that would be invalidate by such tests.

Anyway I ran some tests and the difference (p value of 0.16) means you can't tell that the difference is due to the variable (vaccination) with any sort of certainty

I just saw a Neil deGrasse talk and his musing on the failure of most people to understand data analysis, statistics and probability was hilarious. I suggest you check it out in Starry Messenger: Cosmic Perspectives on Civilization