The Fountain of Youth is Filled With... Coffee?

A new study from an old database suggests that even those who sweeten their coffee outlive those sad souls who don't drink coffee at all.

Having written about abortion and monkeypox the last two weeks, I thought I might have run out of click-worthy subject matter for a while. Thankfully, a new study on coffee’s life-preserving effects gained media traction, and I was saved! Since the world is divided between people who drink coffee and people who don’t and wonder if they’re making a terrible mistake, talking about coffee is always a winner. The question is: should everyone be drinking coffee?

The study inspired a predictable array of kitschy headlines, like this:

I admit, when I saw the headlines, I figured I would read the study and tear it apart. Full disclosure: I have nothing against coffee. In fact, I quite enjoy the half cup I sip each morning while I do my daily Wordle (unless, of course, the Wordle word is “BAYOU,” in which case I enjoy nothing at all). However, it’s rare for anything in this world to have a real survival benefit. If an extremely common drink offered mortality reductions in the 20-30% range, that would be amazing!

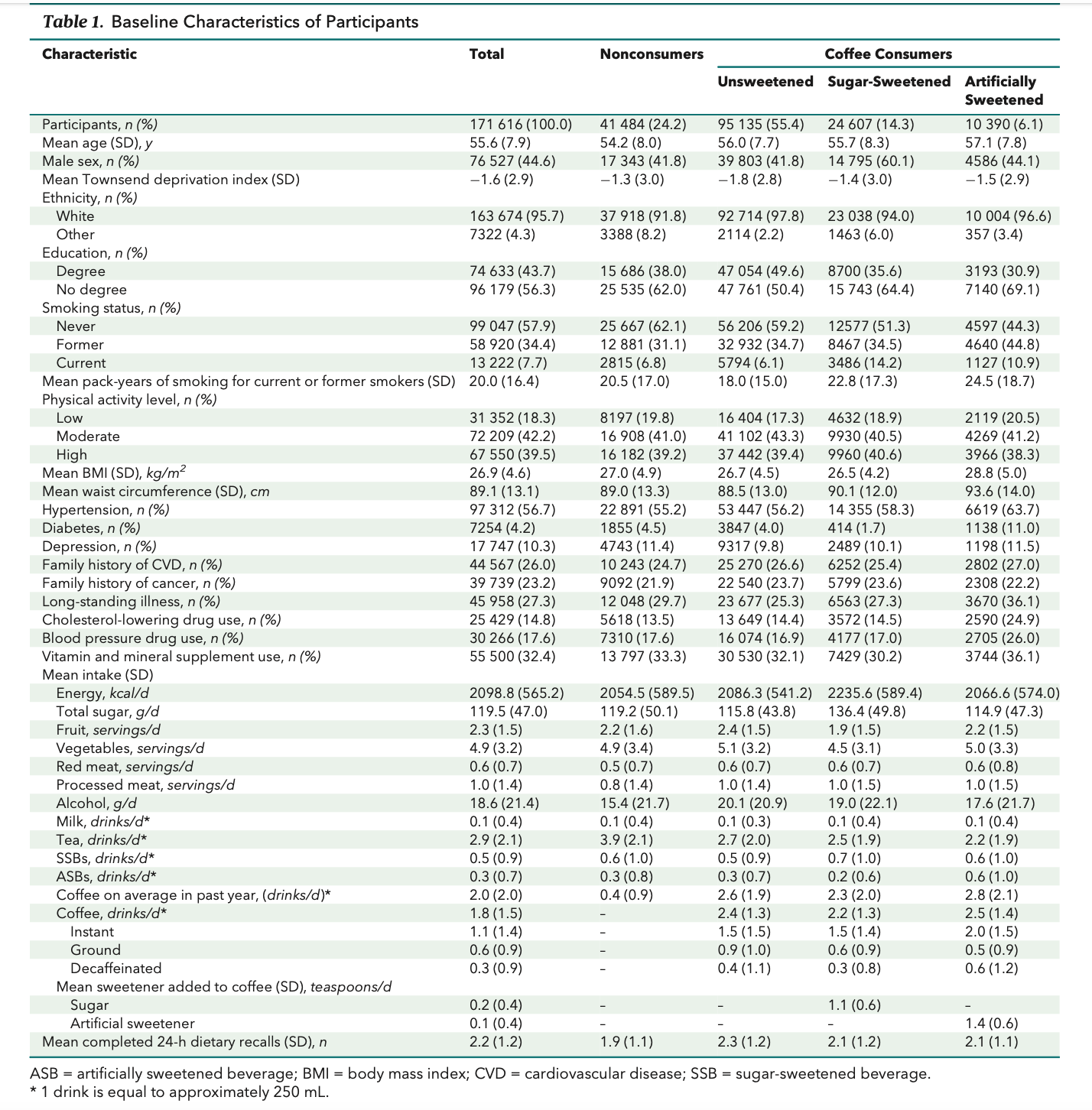

So, having invested $35 in my own private copy of the study, I read it. It’s surprisingly difficult to tear apart. The authors are not on the Folgers Coffee payroll, and I don’t see obvious flaws in their methodology. The data is from the massive UK Biobank. While large (170,000 strong for this study), it might not be totally appropriate to apply to the general public, unless your general public is overwhelmingly white, middle-aged, and interested enough in health to volunteer for a somewhat meddling project like the UK Biobank. Still, we have a decade of information to follow up and see what happened to people based on their initial survey answers as to the amount and type of coffee they drink.

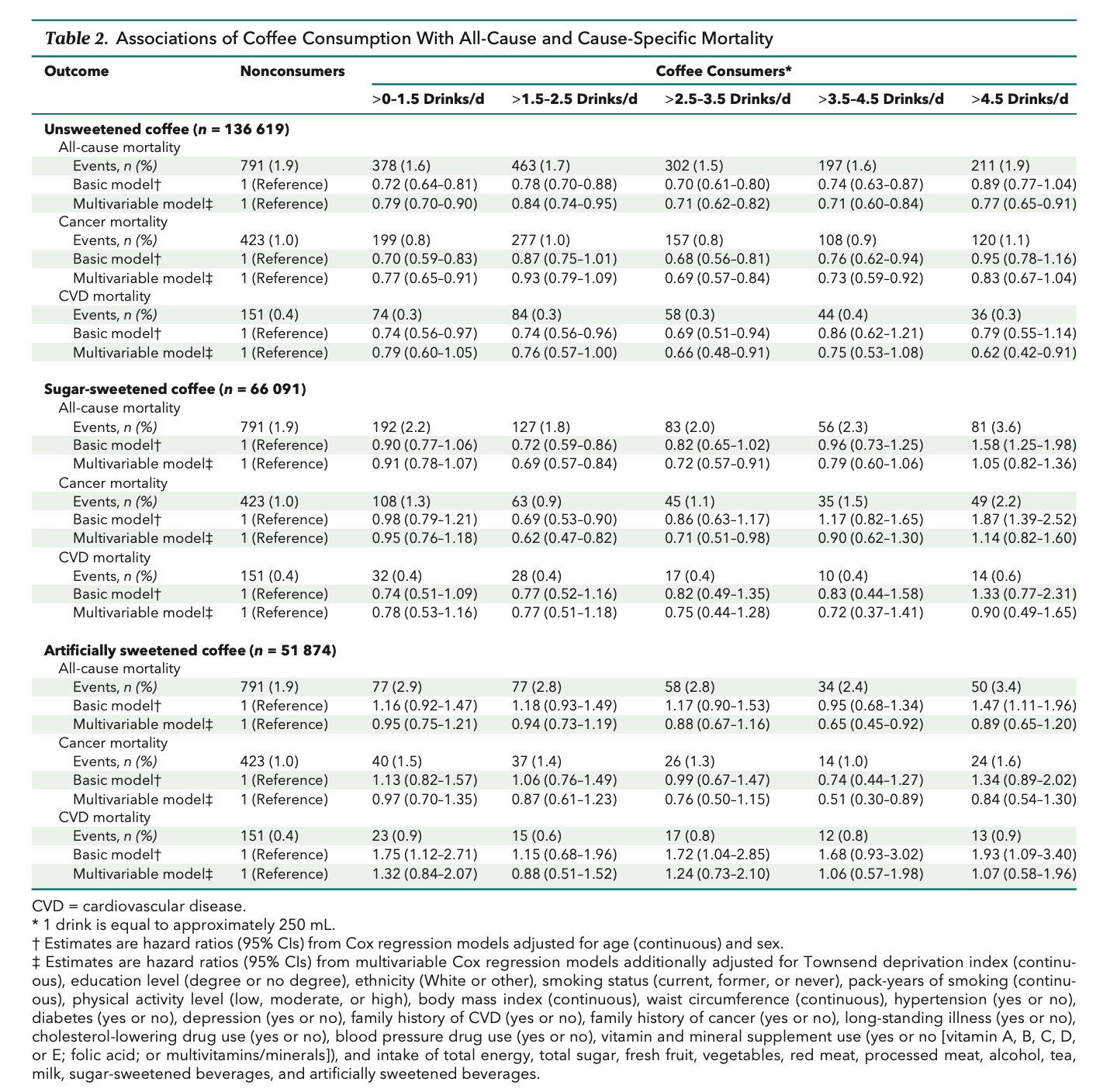

The results were striking. Akin to a 2018 analysis of this same UK Biobank data, those who reported drinking 1.5 to 4.5 cups of unsweetened coffee were some 16-29% less likely to die during the study period than non-partakers. (Drinking less or more was a bit less beneficial.) The wrinkle provided by this study was to assess those who sweetened their coffee with sugar. Rather surprisingly, they had similar mortality benefit, in the 21-31% range, although not always reaching statistical significance. Results for those choosing artificial sweeteners were not much different.

For those who like to review the data for themselves, here it is:

The obvious take on these remarkable figures is to declare them too good to be true, the result of some hidden confounding factors. One might recall the controversy over the “U-shaped curve” of sodium use, in which some studies claimed that very high or very low sodium consumption was associated with higher mortality, but skeptics noted that a certain proportion of the “very low sodium” crowd was simply too ill to sit up in bed and eat french fries. However, can the same be said about coffee drinkers?

If I am honest with myself, I would admit that the most likely confounders would head in the other direction, biasing the mortality to the worse for coffee drinkers. I would expect insomnia or shift work to drive a 3+ cup a day coffee habit, and do consider insomnia and shift work terrible contributors towards death. I might also think that heavy coffee drinkers, given the fairly negative messaging from the health community about coffee until recently, would generally be less health conscious than non-sippers. I can come up with possible confounders that would improve the mortality of coffee drinkers, too, although they seem less potent: coffee drinkers might be more likely to be gainfully employed and have a need to stay alert, for instance.

The authors, of course, attempted to account for these differences, and provide both age and sex adjusted rates, as well as an adjustment for multiple socioeconomic factors. Indeed, in this and other studies, heavy coffee drinkers do tend to smoke more than light coffee drinkers; this trend needs to be accounted for, and mortality for the >4.5 coffees/day crowd improves substantially once smoking is included in the analysis. However, it does not appear that UK coffee drinkers drank fewer soft drinks, weighed less, ate less, consumed less sugar, etc. on the whole than non-coffee drinkers. They just drank less tea. Unless you think black tea equates to the Black Death — which would run counter to studies also finding mortality benefit to tea consumption — it’s hard to make the case that coffee drinkers in the UK Biobank are somehow an inherently healthier crew than non-coffee-drinkers. The details:

For those of you very reasonably saying, “Just because there is no obvious difference doesn’t mean there is no hidden difference,” I can’t disagree. I can say, however, that it’s not just this UK Biobank study finding numbers like this. Similar, although somewhat more modest (in the ballpark of 10%), mortality benefit was found in a longitudinal study of the very, very important sub-group known as U.S. health care workers; as well as in the long-running EPIC study from 10 European countries. Including several smaller studies, all the relatively recent work I found claimed some benefit associated with coffee consumption.

That leaves the million dollar question: could this effect possibly be real? A 20-30% mortality reduction is a big deal; we joke about putting statins in the water supply, and yet are quite pleased when we find a 10% mortality reduction in a 6 year study on statin use in a high risk population. If there is no biological plausibility, the odds go way up that we have been seduced by confounders, bad methodology, or corrupt/inept investigators.

I have a few theories to offer in regard to biological plausibility. Well, every coffee drinker will have the same theory: coffee drinkers have more to live for! That might be said in jest, but there is something about starting each and every day with a beloved, relaxing ritual that might be very good indeed for that all-important balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. This could sound woo-woo, but it’s not altogether crazy. After all, we have seen claims for mortality benefit of a similar magnitude made for warm-and-fuzzy practices like dog ownership. Malcolm Gladwell’s wonderful opening to Outliers reminds us of the possibility that age-old rituals might just outflank Pelotons and on-patent pharmaceuticals when it comes to longevity.

Then there’s the technical stuff. Yes, coffee contains polyphenols like chlorogenic acid with antioxidant properties that have been theoretically tied to health benefits like improving metabolic health and preventing Parkinson’s disease. Coffee drinking might favorably alter the gut biome. It might even improve liver health. Color me skeptical that these properties are so powerful that they could be the main driver in a 10% — or 30% — mortality benefit. They might, however, contribute, and could help explain the apparent dose-dependent response in which the 4 cup a day crowd outperforms the 1 cuppers.

The caffeine content in coffee is a tempting target to which to ascribe its healthful properties: weight loss, better bowel health, dementia reduction, and so on. However, this study, and others before it, also found similar benefits for that saddest of beverages, decaf coffee. So it’s not the caffeine.

The decaf angle strikes at another refuge of the skeptic, that perhaps people who drink a good bit of coffee do so because they have the genetic talent to metabolize caffeine efficiently, and that perhaps this genetic talent is linked to other genetic talents that actually are the cause of the apparent greater longevity of coffee drinkers. In other words, a crappy caffeine metabolizer like me (my heart would literally explode if I drank 3 entire coffees in a morning) would never have a 1.5-4.5 cup per day habit like the eternal souls of the UK Biobank. Perhaps heavy coffee drinkers slug down so much coffee just because they can, but even if they didn’t, they would still outlive us pathetic metabolizers, simply from the great good luck of better genetics.

Possible? Yes. Likely? No. Since some have hypothesized that rapid caffeine metabolism might be tied to better metabolic health, this is not an untested idea. In 2018, another set of investigators interrogated the genomic samples from this same UK Biobank database for evidence that rapid metabolizers who drink coffee might outlive slow metabolizers. Slow metabolizers did just fine. Between that analysis, and the similar mortality results between caffeinated coffee and decaf drinkers, the genetic explanation seems unlikely.

All in all, if coffee were a pharmaceutical compound with observational data like this, U.S. academics would be calling for huge randomized controlled trials to sort out if the third of Americans who don’t drink coffee should start. Unfortunately, finding a few ten thousand non-coffee-drinkers willing to be randomized to drinking 2 cups of coffee a day for 5-10 years might be a challenge, and an expensive one. So, based on this data, am I supposed to start instructing all my patients to drink a couple cups of coffee every day?

I can’t shake the feeling that I’m being played like a violin at the annual saps’ convention. I mean, Contrarian Twitter found the whole thing amusing:

Sigh. Professor Oster might be right. If you start digging through old work on coffee and longevity, the opposite conclusion is reached in multiple studies. However, I do mean, “old.” Here is an example, which began enrollment in the 1950s but the results appear to have been printed by Johannes Gutenberg:

The next batch of studies was a bit more mixed; by the more recognizable fonts of 2012, this New England Journal of Medicine study (enrollment: 1990s) mentioned the variable results from recent years, but was the first large data set to connect more coffee with less death:

Now, it’s one positive study after another, at least for the coffee industry. There could be a unifying explanation. Maybe that canned coffee our forebears drank decades ago was lethal. Perhaps epidemiologists were unskilled at running multivariate analyses in the 1980s on their truck-sized computers and just couldn’t sort out the smoking from the coffee very well. Or maybe as coffee’s reputation became less tarnished, healthier and healthier people began to drink it, until now it’s the drink of choice for health-conscious, fit folks, and the best biostatisticians can’t tease out the inherent wellness of modern coffee drinkers. In a Substack post from last year, Professor Oster makes just this point; we could have a “self-reinforcing bias” on our hands, one which makes observational trials of this nature extremely tricky.

So, what is a poor doctor to do? Perhaps I am being generous here, but in my mind it’s roughly a coin toss if the perfectly designed randomized controlled trial would show a mortality benefit for moderate coffee drinkers. Since we’ll never get that trial, I would encourage my coffee abstainers who have not already failed their own trials of coffee due to palpitations, insomnia, gut intolerance, anxiety, etc., to try drinking 1-2 cups of coffee per day. While one-size-fits-all dietary advice is inherently flawed, since we all have unique genetic, epigenetic and environmental forces acting upon us, individual experimentation with an open mind is sometimes more useful than poring over averages aggregated from datasets of hundreds of thousands of people. An n of 1 coffee experiment? Not much to lose, so much to gain!

I would, however, discourage sweetening their coffee, despite the sunny conclusions of the UK Biobank study, since I see no good coming from teaspoons of sugar. Moreover, the sugar in, say, a Starbucks Caramel Macchiato (33g) is 8 times the sugar in the average Brit’s cup of coffee. I would remind patients that 2 cups of the 8 oz/250ml size from this study is less than one Starbucks 20 oz Venti. Fake dairy sweeteners would be verboten. Most of all, if a trial of coffee drinking leads to any sleep disruption or heart symptoms, just stop.

But if a newly minted coffee drinker finds joy in that hot cup of black nectar, what a cause for celebration! Every extra year my “evidence-based” advice gives them will be so very much more enjoyable.

Coffee is the font of life, come Helvetica or high water.

Add some rich antioxidant chocolate cocoa and you will definitely increase the somewhat murky cardio-benefit of straight coffee; further proving there truly is a God in Heaven who is in charge and who loves us.